Speech delivered at Sheffield University at a conference on imperialism in October 1995

This is most encouraging – a full house – on race and class and black struggle? A full house for what the journal Race & Class stands for? Black and Third World liberation? That’s terrific – at least it makes me feel that those of us who are gathered here today are almost of one accord in believing that poverty and racism are locked in deadly embrace, that racism and imperialism are imbricated in each other, that you cannot separate black struggle from Third World struggle.

And that encourages me to take you into my confidence. It encourages me to say something that I have been dying to say in public – and I think I’ve found at last the audience to whom I could say it …

1. I am fed up with nationalism, culturalisms, ethnicism, cultural politics, identity politics, the quest for personal freedom, personal pleasure to the exclusion of everything and everybody else. What on earth does Black mean if not kinship and community and solidarity? What is the point of all the injustices we have suffered under one sort of racism or another, if we cannot open out to the oppression of others? What is the point of experience if we do not understand its meaning? And what’s the point of knowing its meaning if we do not change the experience? The aim of the individual, Fanon, that great avatar of Blackness, once said, is to take on the universality inherent in the human condition.

And at the other end of the spectrum, we have the post-modernists, who hold that nation, culture, power, state, everything – is transient, fleeting, contingent, that the word is the deed, that representation is reality – the philosophers have interpreted the world, they might well say, our business is to change the interpretation – that there are no grand narratives, no great historical truths, that history itself is ended, in that all opposition to capitalism is ended and capitalism rules the world.

Why do we listen to these people – this craven intelligentsia thrown up, manufactured, by the Information Society, by the communications media? History may well be over for the capitalists and imperialists of the western world, but for the poor and the Black and the Third World, history has hardly begun. And every time we find our history, make our history, they break us from it. Slavery broke us from our history, and when we broke free of that, they gave us colonialism, to break us from our history again – and when we overcame that, we get the New World Order, the new Capitalist Order, the new imperialism where the world is divided into the haves and the have-nots and the never-will-haves; the rich, the poor and the superfluous – euphemistically known in the West as the underclass: a replica of the Third World in the first.

* * *

2. We once understood the importance of reclaiming our history in order to take our struggle further – not to be historicist, not history for its own sake – but to make our struggle relevant to the times we lived in and so take it further. We wanted to know where we came from only in order to know where we were at, and where we were going. And, in the process, we understood the common denominators of struggle that brought us together, united us, Black and Third World peoples, across the globe.

And we had all sorts of expressions of that struggle – in the anti-colonial movement, in the liberation movements in Africa, in the civil rights and Black Power movements in the United States, in the anti-Vietnam war movement. But nowhere have these come together in a clear, straightforward and yet symbolic way, [more] than in this country in the post-war years.

3. Let me remind you. We came here as workers then, most of us, to do the shit work that white workers would not do, in the hospitals and the transport services, in the foundries and the factories, on the streets and on building sites. And we came from diverse parts of the Caribbean and Africa and the Indian sub-continent – but we shared a common experience. On the one hand, we faced a common racism which exploited us all – if differentially – at every turn, and on the other, we brought with us a knowledge of, and a resistance to, the colonising power. And it was those common experiences that forged a unity among us in our struggles against racism – irrespective of whether we were Indians, Jamaicans, Nigerians or Ceylonese – both in the community and on the factory floor – as a people and as a class, and as a people for a class. And that was how Black came to denote the colour of our politics and not the colour of our skins – a contribution that is unique in the annals of post-war anti-racist struggle in Europe (or in the US as a matter of that) and explains why the fight against state racism has been more successful in this country than in France or Holland or Germany or Belgium.

4. The other side of that coin, that concept of Black, was the concept of the Third World. We were, unlike our African-American brothers and sisters, only a generation removed from our land bases, our countries of origin, and we related directly, existentially to what was going on there – there was an uncle, an aunt, a grandparent; the extended family (extended all the way from here to Africa and Asia and the Caribbean) are there – and the struggles there became a part of our struggle here too. A member of the Indian Workers’ Association, for example, could be marching as a member of the Black People’s Alliance against Enoch Powell’s racism on a Sunday; on Monday he might be leafleting in his Indian community about the excesses of Indira Gandhi’s emergency regulations, and as a workers’ representative, he might be negotiating for his branch to get TGWU membership on a Tuesday. We were Indian and Black and working class in different contexts at different times, and sometimes all at once. It caused us no identity crisis: we knew exactly who we were and what we were doing – and in the doing we became who we were. Culture was a way of coming to the struggle (not an avenue of retreat), but the struggle itself was political. Let me put it another way: you might in your life-style define yourself culturally, but in the fight against racism, you defined yourself politically. And in real life, of course, one intruded into the other. A fight around immigration laws, for instance, was also a fight for family life, whether you were African-Caribbean, Asian or African. And what eventuated in the process was not a cultural politics but a political culture.

5. Our connection to our countries of origin also meant an interest in imperialism, a knowledge of a world system, a conviction about the justice of liberation struggles the world over.

Claudia Jones, the editor and founder of the West Indian Gazette, was deported from the US in 1955 for seeking to overthrow the government. Martin Luther King, on his way to Oslo for the Nobel Prize, stopped over in Britain and instigated the founding of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination. Malcolm X, returning from his pilgrimage to Mecca, was urging his audiences in Oxford and in London to internationalise the Black struggle at the very moment that Jan Carew here was bringing out the first issue of Magnet, a political Black newspaper. Black parties in Britain provided the fillip and the personnel to get the first campaign against Portuguese rule in Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique and Angola – off the ground.

6. Look at any Black paper from the ‘60s or ‘70s (the papers I refer to are community, Black party-based non-commercial organising tools, not the kind of thing we have today in Smith’s) – and you will see what I mean. The repressions, world-wide, of non-white peoples – whether in East Timor, Cameroon or Dominica – racism and imperialism, Black and Third World struggles – these were the themes of the papers.

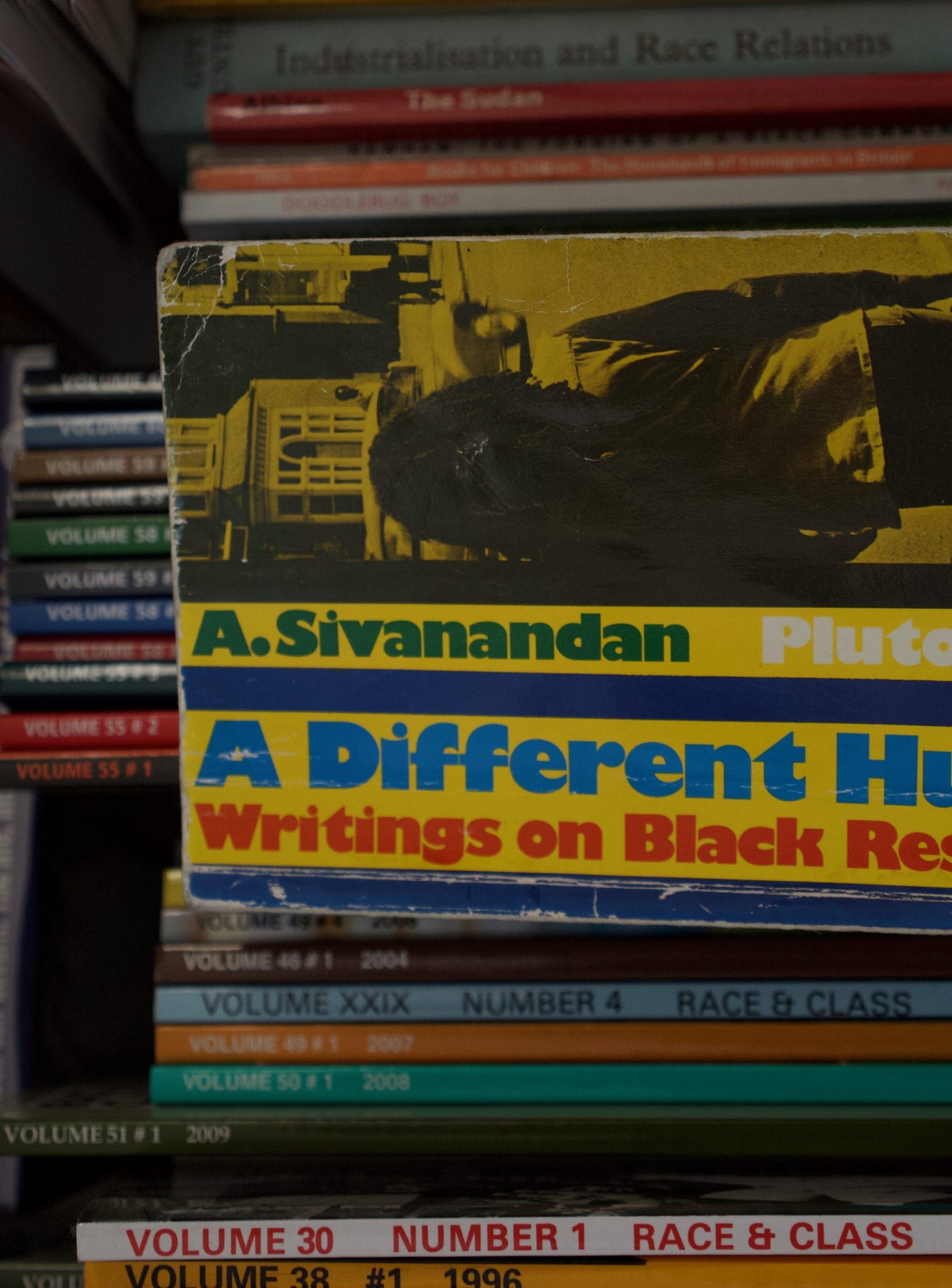

Race & Class was born in that maelstrom when in 1974 (in taking over the IRR), we also took over the arid academicist journal Race and turned it into Race & Class – a journal for Black and Third World liberation.

7. The lines of struggle were clearer then than now, 21 years on. But today, more than ever, we need to make those connections, foment those struggles, kick-start a movement. Because global capitalism is wreaking havoc all over the world and the opposition to it has been all but extinguished. The industrial working class has decomposed under the impact of the technological revolution, so vitiating its collective strength and undermining the labour movement. Communism has gone and killed itself and the liberation movements in the Third World countries have been beaten into the ground. At the same time the centre of gravity of exploitation has moved away from the metropolitan working class to the workers in the periphery – where repressive regimes, set up or maintained by Western powers – some ostensibly parliamentarian, others avowedly authoritarian – have delivered up a cheap and captive workforce to the multinational corporations and the robber barons of international finance: the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

8. And it is this systematic despoliation of our countries – exhausting the earth of its minerals while mutating food-growing land to cash crops and so condemning our peoples to famine and hunger; structuring programmes that consign our children to illiteracy and a lifetime of un-education (they call it Structural Adjustment Programmes) while at the same time seducing our intelligentsia with scholarships and fellowships in the land of the brave and the home of the free; and setting up dictatorships to bring all this about while exploding ethnic and nationalist wars for which the ground has already been laid – and mined – in colonial times.

9. And these in turn have led to the massive displacement of whole populations within and between Third World countries and continents, and thrown up political refugees and asylum seekers on the shores of Europe and America.

And yet the governments of the West continue to maintain that these are economic refugees and not political refugees.

Take the case of Anthony Edeh, for instance, who is being held in the most inhuman conditions in a container ship off Bremen harbour. (His case is being taken up by the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism, whom you can contact on the stall outside if you want to support it.) His crime was that he had fled from the military dictatorship in Nigeria to claim asylum in the West. Edeh had been a political adviser to the Nigerian Oil Workers’ Union, and he was fighting for the rights of the Ogoni people whose lands were being systematically destroyed by multinational oil corporations. Trade unionists, fighters for democracy, Ogoni leaders have been systematically repressed – jailed or murdered by the Nigerian dictatorship, and yet Germany wants to deport Edeh and return him to his death, in the same way as the British government returned Tamil refugees to theirs. And the West still continues to supply arms to the Nigerian dictatorship.

And this is not the only case of unjust, illegal deportation – in my view there are no illegal immigrants, only illegal governments – but they are all based on the specious arguments of Western governments that these are economic refugees and not political refugees – as though their economics can be separated from their politics, as though the armaments they sell and the regimes they set up have nothing to do with their insatiable drive for profit and yet more profit. As though anyone is all economic or all political, even a refugee. I have trouble myself in finding out which part of me is economic and which part of me is political.

But I do know one thing – that all of me is refugee and immigrant and Third World and Black. And it is in the remembrance of these things – the things that we are – that we can connect again with the plight and problems of present-day refugees and asylum-seekers – and through them understand the Third World again, our land bases again, in a visceral, existential way – in, that is, through fighting alongside them for their rights and their justice, and therefore for ours – in their countries and here, both at once.