This is a revised version of a talk given on 12 March 1983 at the Greater London Council Ethnic Minorities Unit Consultation on Challenging Racism. First published in Race & Class 25/2, Autumn 1983.

I am delighted that I have been asked to speak here today because what I want to say has to be said here, under the auspices of the GLC’s Ethnic Minorities Unit – here in this very temple of ethnicity – because I come as a heretic, as a disbeliever in the efficacy of ethnic policies and programmes to alter, by one iota, the monumental and endemic racism of this society.

On the contrary. What ethnicity has done is to mask the problem of racism and weaken the struggle against it. But then, that is precisely what it was meant to do. It was the riposte of the system — in the 1960s and 1970s — to the struggles of black people, both Afro-Caribbean and Asian, both in the workplace and in the community, as a people for a class – extra-parliamentary and extra-trade union. It was the riposte of a system that was afraid that the black working-class struggles would begin to politicise the working-class as a whole. It was, in particular, the riposte of the class-collaborationist Labour governments of Wilson and Callaghan who sought in ethnic pluralism to undermine the underlying class aspect of black struggle and black politics. But the massive onslaught of Thatcherite Toryism on blacks and the working class has shown Labour — or, at least, the Labour councils in the inner cities – the error of their ways and the inadequacies of multiculturalism to combat the new racism. There is room for manoeuvre here, for a war of position if you like – and it is up to the black communities to return ethnic struggle to black struggle and socialism to Labour.

To work out the more immediate and short-term strategies, therefore, we need to go back into our history, black history, in this country and look at the changing nature of racism, the corresponding changes in the sites and locales of struggle – and in the process take a closer look at how the language of struggle was changed from anti racism to multiculturalism.

Racism does not stay still; it changes shape, size, contours, purpose, function – with changes in the economy, the social structure, the system and, above all, the challenges, the resistances to that system. And to understand the dynamics of this racism and its relationship to the class forces in society, I want to take you back to the 1950s and 1960s.

Racialism versus racism We came here when a war-torn Britain needed all the labour it could lay its hands on. It had stock-piled, through exploitation and another racism, whole reserves of cheap black labour in the colonies and it was inevitable that the countries in which they were stock-piled should sup ply Britain with the labour it needed for its factories and services. So that what we came to in the early period of the 1950s was a kind of laissez-faire discrimination and a racialism, a racial prejudice, which carried over from the colonial period. It was not structured, institutionalised — though colour was written into discrimination: the system discriminates in order to exploit, in the process of exploiting, it discriminates. Because Britain needed all the labour it could get, the discrimination that obtained was in terms not of getting jobs but rather in our social life, in housing, schooling and so on. We faced a racial discrimination which depended on market forces. Colour only gets written into legislation via the Immigration Act of 1962; and from then on it begins to get institutionalised. And that is a crucial difference: the difference between the racialism of the earlier period and the racism we begin to confront from 1962 onwards. It is a difference abjured in the higher reaches of sociology and by avant garde ‘theoretical practitioners’ of the left. But it is a distinction we need to make if we are going to understand how to sort out the struggles against people’s attitudes and the power to act out those attitudes in social and political terms. It is an essential distinction to make for the purposes of practical struggles and, as you will see, a distinction that came out of struggle. People’s attitudes don’t mean a damn to me, but it matters to me if I can’t send my child to the school I want to send my child to, if I can’t get the job for which I am qualified and so on. It is the acting out of racial prejudice and not racial prejudice itself that matters. The acting out of prejudice is discrimination, and when it becomes institutionalised in the power structure of this society, then we are dealing not with attitudes but with power. Racism is about power not about prejudice. That is what we learnt in the years of struggle in the 1960s – when we met it in the trade unions, on the shop-floor, in the community, at the ports of entry. We learnt it as we walked the streets, in the social and welfare services, in the health service — we learnt it everywhere. And inevitably our struggles involved all our peoples and all these areas.

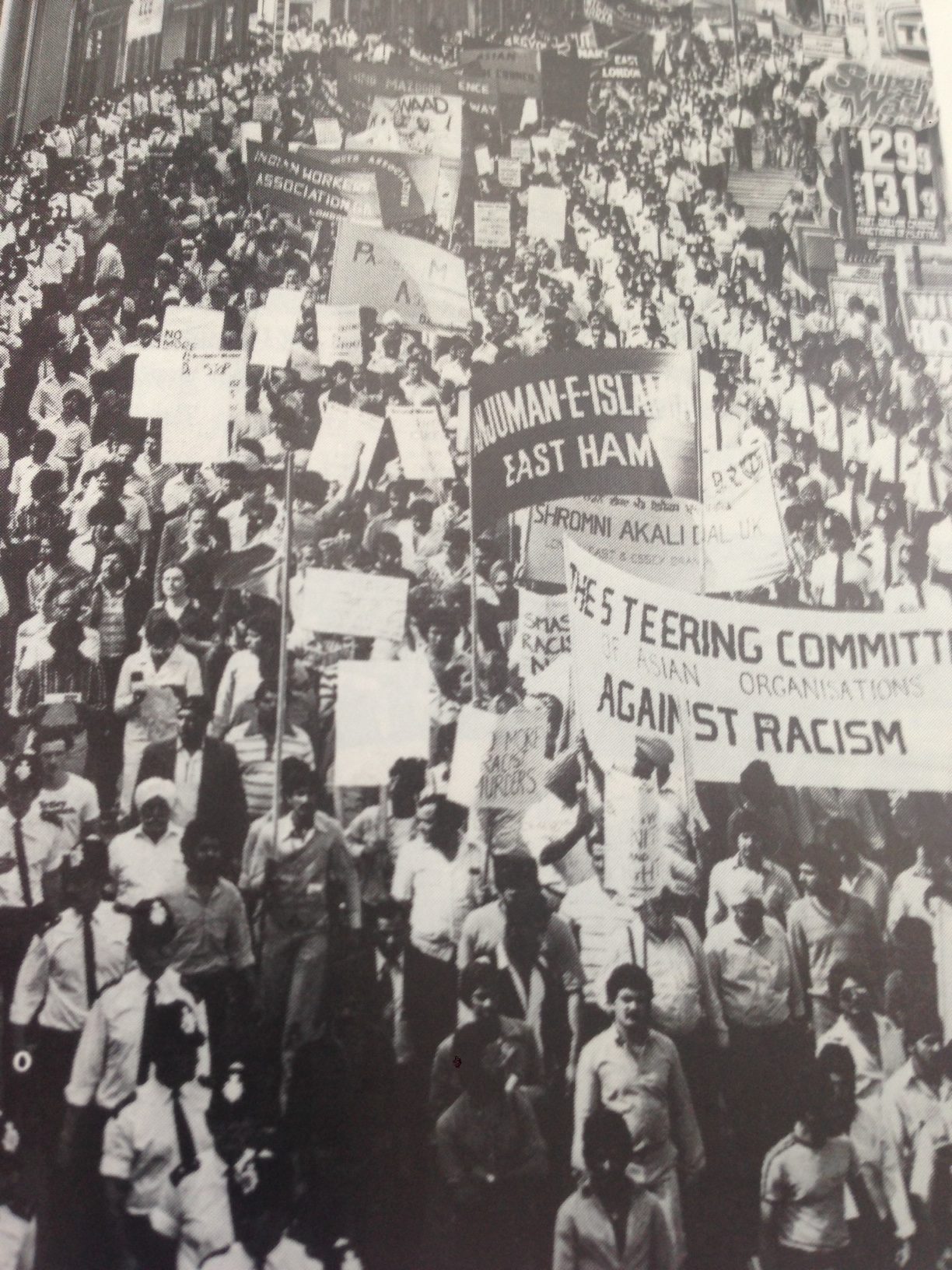

Black infrastructure In the workplace and the community, Afro-Caribbean and Asian, we were a community and a class, we closed ranks and took up each other’s struggles. We had such a rich infrastructure of organisations, parties and self-help projects. Self-help was what we did, exactly, because we were outside mainstream society. We built a whole series of projects which grew out of organisations in the community. And all the parties, like the United Coloured People’s Alliance, the Black Unity and Freedom Party, the Black Liberation Front, the Black Panthers, had their projects, newspapers, news-sheets, schools. Organisations went to the factories and the strikes were taken from place to place — strike committees up and down the country learning from one another – and learning in the process to weave from the differing but common traditions of our anti-colonial struggle a common struggle against racism. We related both to the struggles back home and the struggles here, the struggles then and the struggles now, the struggle of Gandhi and Nehru, of Nkrumah and Nyerere, James and Williams, of Du Bois and Garvey – and the ongoing struggles in Vietnam and Portuguese Africa’, in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde – and the struggles for Black Power in the United States of America. They were all a part of our history – a beautiful massive texture that in turn strengthened the struggles here and fed back to the struggles there – and of course we were involved in the struggles of the oldest colony, Ireland. And black was a political colour.

Defensive struggles But as the 1970s began to dawn and the recession began to bite, labour was being laid off. It was a period on the international scene when capital was moving to labour in Third World countries, instead of importing it to the metropolis. It was a period when Britain, like the rest of Europe, no longer needed cheap black labour. The Immigration Act of 1971 stopped all immigration dead, breaking up families and damaging the whole fabric of family life; the ‘Sus’ laws criminalised the young – and our priorities became separated. The Asian community, by and large, was concerned to get their dependants in before the doors shut on them; and struggles had to be waged too against arbitrary arrests and deportations. And because these were legal issues, issues connected with the law, the Asian community tend ed to take them on in a very legal way, a defensive way, through law centres and defence committees – one-off committees which no longer collated and co-ordinated struggles. The concern of the Afro Caribbean community, on the other hand, focused predominantly around issues like ‘Sus’ and the criminalisation of their young, police brutality and judicial bias. That is not to say that there were no struggles in the work-places (take Imperial Typewriters, STC or Perivale Güterman, for example) or that Afro-Caribbeans and Asians did not continue to make common cause. But we did not have the newspapers which would have coordinated those struggles, we did not have the political organisations which had produced the papers.

The infrastructure we had built up was being eroded. It was only the black women’s movement that continued from the 1970s and into the 1980s to hold together the black infrastructure. It was the women — both Afro-Caribbean and Asian — who were to continue to collate the struggles, to connect with Third World issues, to publicise and organise and, above all, uphold the unity between Asian and Afro-Caribbean communities.

Ethnicity blunts black struggle At the same time, on the ideological level a new battle was being mounted by the state against black struggles whereby they could be broken down into their ethnic and, through that, their class components. Ethnicity was a tool to blunt the edge of black struggle, return ‘black’ to its constituent parts of Afro-Caribbean, Asian, African, Irish – and also, at the same time, allow the nascent black bourgeoisie, petit-bourgeoisie really, to move up in the system. Ethnicity de-linked black struggle – separating the West Indian from the Asian, the working-class black from the middle-class black. (And a certain politics on the black left itself was beginning to romanticise the youth, separating their struggle from those of their elders — destroying the continuum of the past, the present and the future.) Black, as a political colour, was finally broken down when government monies were used to fund community projects, destroying thereby the self-reliance and community cohesion that we had built up in the 1960s.

Ethnicity began life as a pluralist philosophy of integration – ‘equal opportunity accompanied by cultural diversity in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance’ -floated by the then Home Secretary Roy Jenkins in 1967 and taken up by the other Roy, Hattersley, and by all the other boys and girls of the labour movement, and transformed into ethnic policies and programmes by the pundits of the Community Relations Commission, the Race Relations Board and the Runnymede Trust, aided by bourgeois sociologists and educationalists, and funded by the Home Office’s Urban Aid Programme. Government monies for pluralist ploys — the development of a parallel power structure for black people, separate development, bantustans – a strategy to keep race issues from contaminating class issues.

Where that pluralist philosophy was first put into effect — where it was formulated and defined — was in education – in the schools – precisely because it was there, among the young blacks, the ‘second generation’, that the next phase of revolt was fermenting. And the name of the game was multicultural education.

Now, there is nothing wrong with multiracial or multicultural education as such: it is good to learn about other races, about other people’s cultures. It may even help to modify individual attitudes, correct personal biases. But that, as we stated in our evidence to the Rampton Committee on Education, is merely to tinker with educational methods and techniques and leave unaltered the whole racist structure of the educational system. And education itself comes to be seen as an adjustment process within a racist society and not as a force for changing the values that make that society racist. ‘Ethnic minorities’ do not suffer ‘disabilities’ because of ‘ethnic differences’ – as the brief of the Ramp ton Committee suggests – but because such differences are given a differential weightage in a racist hierarchy. Our concern, we pointed out, was not with multicultural , multi-ethnic education but with anti-racist education, which by its very nature would include the study of other cultures. Just to learn about other people’s cultures is not to learn about the racism of one’s own. To learn about the racism of one’s own culture, on the other hand, is to approach other cultures objectively.

But multiculturalism has become the vogue; it gives the ‘ethnic’ teachers a leg up and it exculpates the whites: they now know about my culture, so they don’t have to question their own. Worse–and this was demonstrated clearly in a confrontation we recently had with a group of head-teachers who stumbled on the Institute in the course of their multicultural expedition – they know more about my culture than I do, or think they do! And this gives them a new arrogance, based no longer on feelings of superiority about their culture but on their superior knowledge of mine. One sahib even tried to talk Hindi to me —- and I don’t even know the language.

Education, however, was not the only area in which culturalism abounded. It began to spread to other areas too – like the media and policing – but let’s look at these at a later period, after Thatcher’s ascendancy, when they become more clearly defined.

Thatcher: the sites of struggle

The pluralist philosophies and ethnic programmes which had begun to set up parallel (ethnic) structures within society were, of course, part of Labour policies. What happened when Thatcher came into power was that she couldn’t give a damn about blacks or pluralism or the working class. The Tories, in fact, had stolen the clothes of the National Front and moved this society so far to the right as to be near-fascist. (That is why the NF does not do well in the elections; they do better on the streets – look how racial attacks have become part of the popular culture, with the state as a party to it.)

Thatcher herself began life, her racist life – and she is a sincere racist – with a clarion call to the nation to beware that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture’ – a call which unleashed the fascist maggots of the inner-cities on our children. Her policy-makers spoke of internal controls and passport checks. Enoch Powell, the Permanent Minister of Black Affairs, spoke of ‘induced repatriation’ and local Tory authorities like Slough literally paid black people to go home.

The nature and function of racism was beginning to change. The recession and the movement of capital to the labour reserves of the Third World, as I pointed out before, had stopped the importation of labour. The point now was to get rid of it. Hence the rationale of racism was no longer exploitation but repatriation, not oppression but repression – forged on the ideological level through the media (directly) and the schools (indirectly and long-term) and effected on the political level through the forces of law and order: the police and the courts principally.

The sites of struggle, in other words, had moved from the (predominantly) economic to the ideological and political, and the protagonists were no longer the state and the first generation’ but the state and the ‘second generation’, no longer employers and workers but the state and the workless.

And so the locale of struggle moved from the factory floor to the streets, from the one-time employed, now unemployed, to the never employed. And that is a very important distinction to make when we talk about black youth – for they have not only, like their white counter-parts, never been socialised into labour and therein found some stake in the system, but have, unlike them (their white fellows that is), been kept out of work and indeed of society by the dictates of institutionalised racism. And so they take nothing as given, everything is up for question, everything is up for change: capitalist values, capitalist mores, capitalist society. And their struggles find a resonance in the struggle of the unemployed white youth and the cities burst a-flame.

And it is then – after the burning of Brixton and Toxteth and Southall – that Thatcher sends for Scarman to rescue ethnicity for the Tory Party and create another tranche of the ethnic petit-bourgeoisie, this time in the media and the police consultancy business: chiefs for the bantustans.

Just look at the ethnic media today – especially the ethnic television (newspapers and radio programmes were there before, though in a smaller way). Look at ‘Black on Black’ and ‘Eastern Eye’ in particular. On the one hand, we have the idea of letting blacks get places, so that they can teach their young that they don’t have to take on the system when they can become part of it. On the other hand, we have the idea of positive black culture, with Eastern cookery classes and Indian films, reggae and black humour’. These programmes merely replicate the white media; black plays and comedies do the same. “No Problem’ is a problem: we are laughing at ourselves. The system wants that type of replication and “balance’, presenting both sides of a question, as the BBC says it does. What we want on ‘Black on Black’ and ‘Eastern Eye’ is an unbalanced view. We don’t want a balanced view. The whole society is unbalanced against us, and we take a programme and balance it again?

Look at what ‘Eastern Eye’ did with the John Fernandes case. Fernandes, if you remember, is the teacher who exposed the extent of racism in police cadets and in the teaching at Hendon Police College when its head, Commander Wells, refused to accept Fernandes’ findings. ‘Eastern Eye’ gave both Fernandes and Wells a hearing and then, for good measure, allowed Wells the benefit of two black cadets (an Asian and an Afro-Caribbean, a man and a woman) who denied there was any racism at Hendon Police College. That’s ethnicity for you. And the worst of it is that these media wallahs think they got up there on their own merit or because they huddled together and called themselves a trade union. Whereas the fact of the matter is that they got there on the backs of the kids who burnt down Toxteth, Brixton and Southall.

So too have the rebellions of 1981 helped to get more Afro Caribbeans and Asians into the police force. Some police chiefs have even brought down standards of recruitment in the cause of ‘positive discrimination’ – all part of the Scarman scheme. And there are the community consultative committees, with blacks on them to help the police to police the community – a Scarman production, of course.

Such consultative committees should, in fact, be seen in the larger context of the other ‘consultations’ that are going on – between the police and the social and welfare agencies of the state – what is fondly termed community policing. But once Metropolitan Commissioner Newman’s neighbourhood watch schemes get off the ground, spying too will be open to Thatcherite private enterprise.

The information society These developments alone tell us why it is important to take on That cherism on the ideological and political terrain. But there are other more fundamental reasons connected with the massive changes in the capitalist system itself, which makes these two areas paramount. I do not agree with Ken Livingstone* that there is ever going to be full employment again. Full employment is a thing of the past, an artefact of the industrial revolution. What today’s micro-electronic revolution predicates is unemployment. With the silicon chip, microprocessors, robotics, lasers, bio-genetics and so on, we are moving into an entirely different ball game, a different capitalist order if you like, where the division of labour is between the skilled and the unskilled and the classes are increasingly polarised into (simply) the haves and the have nots. Of course, the technological revolution can also make for a society in which there is greater productivity with less labour (fairly distributed) improved consumption for all and more time to be human in. But Thatcher and monetarism do not allow for such a scenario. In stead, what you will have is micro-electronic surveillance, computerised data and centralisation of information — and Big Sister watching you. In such a society — and we come to the same conclusion as when we viewed it from the other direction, through the prism of racism — ideology and politics become paramount. The sites of our struggle, therefore, are in education and the media, on the one hand, and against Tory law and order, on the other — meaning not just the police, but un just laws as well, laws which repress trade unions, women, gays, children and call for extra-parliamentary struggle.

And in that connection, we must not overlook the one positive thing that Thatcher has done — which is to throw up the contradictions within the Labour Party and move certain sections of it closer to us. Remember that the pluralist politics of division which emerged in the 1960s and 1970s came out of the Social Democratic wing of the Labour Party. The left wing (as it began to emerge) has been left with the ethnic baby; it does not know in which direction to turn, and I think that it is up to us to point them in the right direction. Don’t let’s be purists and stand outside, for we can’t fight the system bare-handed. We don’t have the tools, brothers and sisters; we’ve got to get the tools from the system itself and hope that in the process five out of ten of us don’t become corrupt. If we’ve got to get the tools and Ken Livingstone’s GLC is prepared to give them, we should not hesitate to use them.

Programmes and strategies

Now I’d like to go, quickly, into the programmes and strategies of struggle. In the field of education, as we have seen, it is important to turn ethnicity and culturalism into anti-racism. But this involves not just the examination of existing literature for racist bias (and their elimination) but the provision of anti-racist texts — like the two booklets, Roots of racism and Patterns of racism, that we at the IRR have published — and not just an examination of curricula and syllabuses but of the whole fabric of education: organisation and administration, methods and materials, attitudes and practices of heads and teachers – the whole works.

Similarly, in the media we need not only to combat racist bias, but stop replicating the white media and propagate instead radical black working-class values. To do that, ethnic programmes (the English language ones anyway) will have to stop tackling only ethnic themes and look at every aspect of British society from the vantage point of the black experience. Conversely, we should demand to introduce black views and analyses into the main-line programmes (like ‘Panorama’ or “Weekend World’) without being shoved off into ethnic slots.

Other speakers have already spoken on the police and on the Police and Criminal Evidence Bill which will extend to the rest of the population — certainly in the inner cities – the harassment and brutalities hitherto inflicted on the black communities. Here I want only to point out that even while local Labour authorities are making every effort to make the police accountable to elected police committees, the police themselves have deftly side-stepped the issue – first, as we have seen, by their version of ‘community policing’, and second, through media legitimation of their actions. And, if you remember, it was ex-police chief Sir Robert Mark who made the studied cultivation of the media a central aspect of police policy. The GLC’s police monitoring groups are, of course, looking into the whole question of police accountability, and we ourselves are doing research into the media and the police; but, if the Fernandes case is anything to go by, we need to look too at the training for that accountability — for how can we expect cadets trained in racism to be accountable to local black communities?

Cases into issues The Fernandes case also suggests another strategy that we must look to: the turning of cases into issues. Cases are one-off, local, disconnected; issues are national and anti-state. The trial of the Bradford 12, for instance, brought to national prominence the issues of self-defence and conspiracy law; the murder of Blair Peach at the Southall demonstration brought into question the role of the Special Patrol Group and the validity of internal police investigation; the New Cross Massacre and the case of Colin Roach showed, among other things, the bias and inadequacies of the coroner’s court.

We need to concentrate on cases which raise a number of issues and so bring together the various aspects of our struggle and the different groups involved in them. The Fernandes case, for instance, raises a number of issues –education, policing, the media, trade union racism* — thereby providing us with a more holistic view of our struggle and a basis for mutual support and joint action.

And we need to mobilise blacks everywhere around our common experiences of racial attacks. Colin Roach should not just affect Stoke Newington – we should look at the whole aspect of struggle around Colin Roach, the Newham 8, the attacks in Sheffield, in Leicester. We must collate our struggles, cross-fertilising the Afro-Caribbean and Asian experiences, and find unity in action.

We must look, too, to the various levels of struggle — on the streets, in the media, in the council chamber. We must begin to see how we can take our issues into the media and make the media responsible to the communities, instead of legitimating the actions of the system. Similarly, we must make our black councillors responsible to us – they must be seen on the ground participating in our struggle (not just exposing themselves to it), using whatever power they have for the benefit of the community. We must make the black petit-bourgeoisie, which is a petit-bourgeoisie on (white) sufferance, return its expertise, power and education to the working-class blacks whom ethnicity has left defenceless.

Alliances and autonomy And, finally, we must look at the whole area of alliances. Against Thatcherism, there is no question that the objective conditions are there for all sorts of alliances — and alliances do not mean the subservience of one group to another. But, at the same time, we must beware the opposing tendency — and it is a contradiction that has been growing for some time – of too much autonomy. In the 1970s black people said they would not subsume their struggle to the class struggle, that their struggle had got to be autonomous, But we made alliances with the white working class. For instance, during the trial and imprisonment of the Pentonville Five, when the trade unions were planning a march on Pentonville Prison, they appealed to black groups to join in the march. The Black Unity and Freedom Party agreed that the unions’ struggle was also black people’s struggle, but because of trade union racism they would not join the official march. Instead, they led a different march down a different road to the same spot on behalf of the Pentonville Five. That is what I mean by autonomy and alliances.

Too much autonomy leads us back into ourselves; we begin to home in on our cultures as though nothing else existed outside them. The revolutionary edge of culture that Cabral spoke of is taken away, leaving us with a cultural nationalism that is ineffective in terms of social change. The whole purpose of knowing who we are is not to interpret the world, but to change it. We don’t need a cultural identity for its own sake, but to make use of the positive aspects of our culture to forge correct alliances and fight the correct battles. Too much autonomy leads us to inward struggles, awareness problems, consciousness-raising and back again to the whole question of attitudes and prejudices.

Alliances between the anti-racist and the working-class struggle are crucial, because the struggle against racism without the struggle against class remains cultural nationalist. But class struggle without race struggle, without the struggles of women, of gays, of the Irish, remains economistic.

Let me end by saying this: it’s still possible to make use of the good offices of left-wing Labour councils and the ethnic minorities units which left-wing councils have got landed with and turn them towards anti-racist struggle. We must return ethnicity to anti-racism and socialism to Labour. And, in order to do that, we must begin, now, to collate and co-ordinate our struggles – so as to build, in 1984, here, in London, a mass movement. Why not?