Ghetto of the mind

Book review published in New Society April 1971

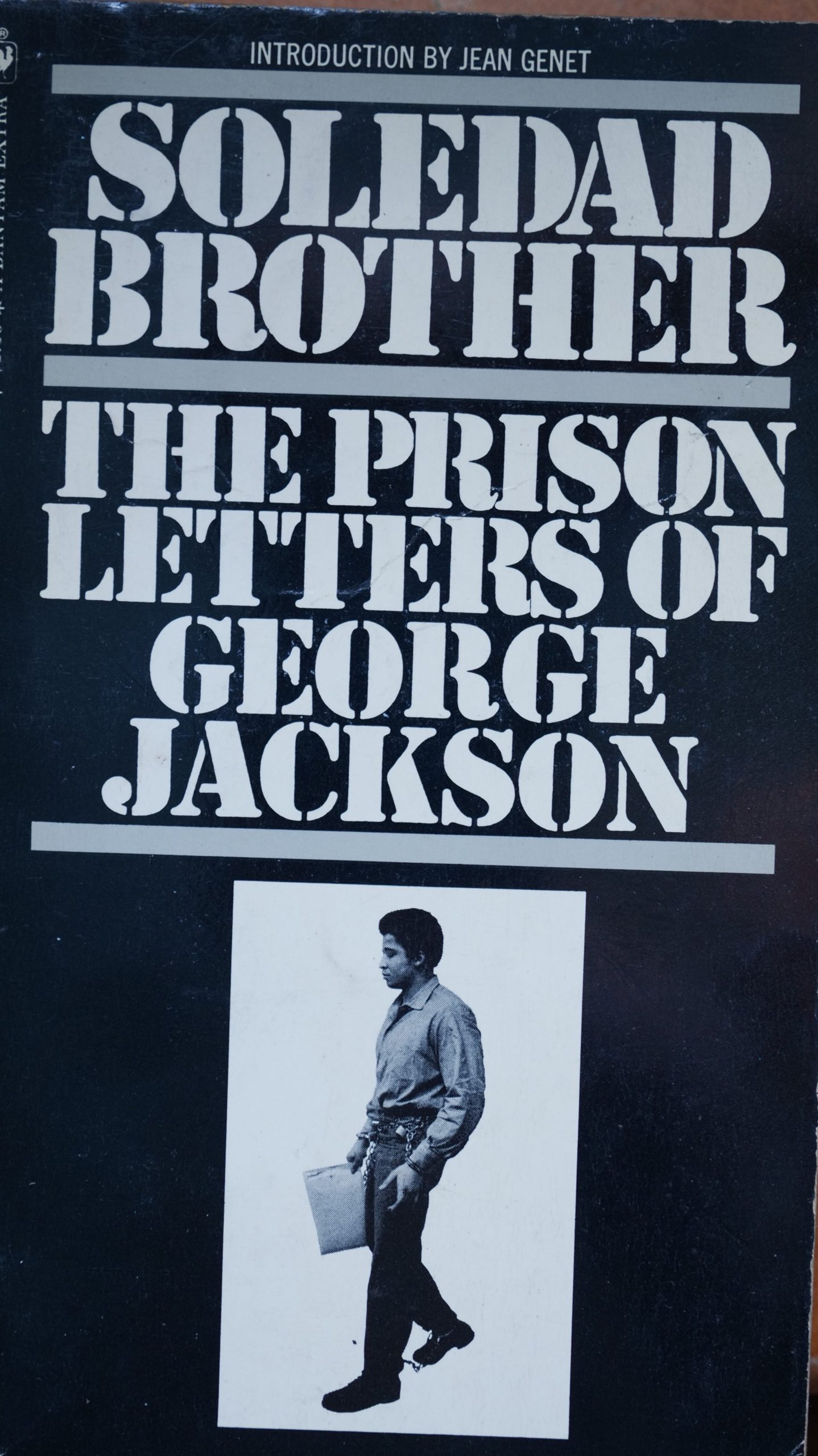

America is insane. An 18 year old robs a petrol station of $70 and ends up in a state penitentiary with a ‘one year to life sentence’.

He then begins to rehabilitate himself: reads anthropology, history, politics, learns Chinese and Swahili, teaches himself maths and electronics-investigates his own life and the life of his people, and questions the system that condemned them to the ghetto in the first place-and discovers that, although the larger solutions must await is release, he may. at least, act out his manhood now: say “no” to injustice, brutality and racist repression wherever he found them.

But Soledad and San Quentin and Folsom never intended that sort of rehabilitation, least of all for their black inmates. And so, almost eleven years later (over seven of them spent in solitary confinement), George Jackson remains in prison-with, now, a mandatory death sentence hanging over him for the alleged murder of a white prison guard.

The letters in this collection, which span the period 1964-70, chart the spiritual and political growth of an extraordinary man, a sort of combination of St.John of the Cross, Malcolm X, and and one’s father. “I have enlarged my vision”, he writes to his mother in June 1964, so that I may be able to think on a basis encompassing not just myself, my family, my neighbourhood, but the world.” To his father he writes: “It is not important how long I live. I think only of how I live, how well, how nobly.” In his correspondence with his womenfolk he discloses a multitude of lovers- a capacity for love unending. Of forgiveness. he writes. “every day I have the opportunity to practise this almost god-like facility. I am human and I have myself done things that require forgiveness from others” And, in “the dark night of the soul,” he reaches down within himself for his resurrection.’I call on myself, have faith in myself. This is where it must always come from in the end.”

But this faith, Jackson realises, belongs to the new breed of blacks. His parents and their generation had lived their entire lives “in a state of shock”- confused and confounded by a world they knew they did not make, that they feel they cannot change.” And so Jackson exhorts them to disabuse their minds of their “natural” inferiority, to stop blaming themselves for their children’s lot. He exalts their virtues. chides them for their weaknesses, urges them to become whole again. Himself imprisoned, he seeks to set them free from the ghettos of their minds.

But the solution, ultimately, has to be a political one. Imperialism had taken over where slavery had left off. The capitalist system denigrated all human life-black as well as white. White culture. white institutions, even the white prison system were only the manifestations of capitalist exploitation A “blanket indictment of the white race” would only confuse the issues further. It was capitalism itself that had to he wiped out root and branch. The activist phase of the task, however, Jackson was content to leave in the hands of Huey P Newton. “our son and brother,” and Angela Davis “my tender experience.” His own contribution would be to prepare and commit Jonathan, his “young courageous brother whom I love more than l love myself” to the revolutionary barricades.

On 7 August 1970 Jonathan Peter Jackson was shot dead while attempting to free a black prisoner and take the judge hostage from the Marin County courthouse. His last words were “All right gentlemen, I am taking over now.”