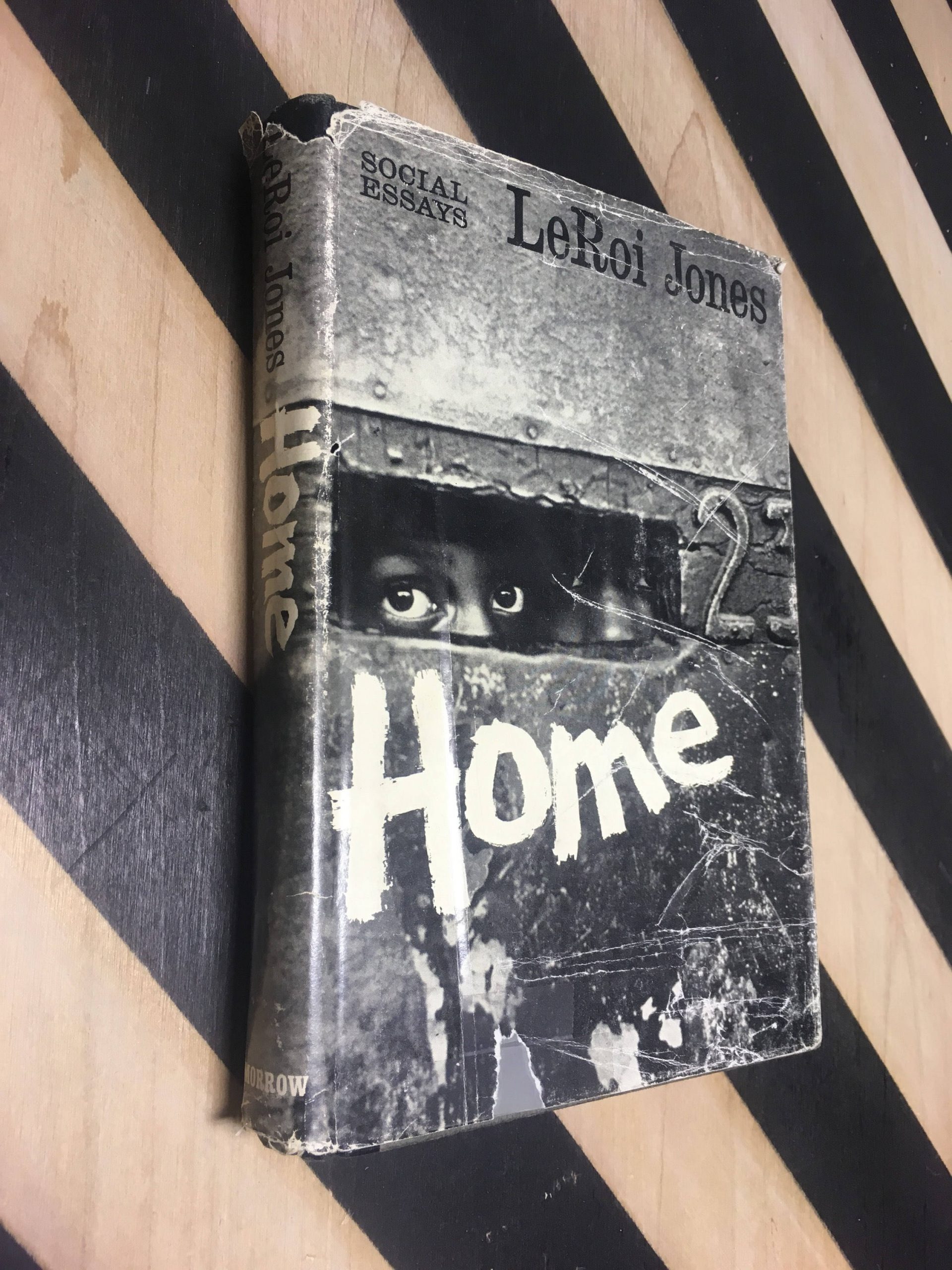

Home: social essays by LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka)

It was ’endless questioning’ Baldwin tells us that ’gave him himself’- and himself, he ultimately found, was American, no narrower than that. But it took him many years of exile before he could make that discovery, before he found out in what way the sheer Negroness of his experience could be made ’to connect [him] with people instead of dividing [him] from them’, before in fact he could attain to that vision of the creative artist which sees the immediate in terms of the eternal.

For LeRoi Jones, on the other hand, ’the holiness of life is the constant possibility of widening the consciousness’, and that consciousness he found early on could not be any more than that of any other Negro in the land. He would, like Stephen Daedalus, attempt to ’forge in the smithy of [his] soul the uncreated conscience of [his] race’. But in 1960, which is the date of his first essay, he was still looking for himself.

’Cuba Libre’, the first piece in Home, which covers the period 1960-1965, describes the liberation of LeRoi Jones himself. On his visit to Cuba in 1960, the author meets a Mexican (woman) delegate to the Youth Congress who is furious that he should condemn American society but should himself do nothing to change it. ’I’m a poet,’ he pleads, ’what can I do ? I write, that’s all, I’m not even interested in politics.’ To which ’a wild-eyed Mexican poet’ replies, ’You want to cultivate your soul? In that ugliness you live in, you want to cultivate your soul? Well, we’ve got millions of starving people to feed, and that moves me enough to make poems out of.’

From there on the essays are, as he himself says, a chronicle of how his mind and his place in America have changed over the years and led him finally towards his belief in black separatism. But in 1962 he was still able to write: ’We are Americans, which is our strength as well as our desperation. The struggle is for independence, not separation….’ And art, he was saying, about the same time, ’must be produced from the legitimate emotional resources of the soul in the world’. Negro literature must disengage itself from ’the weak, heinous elements of the culture that spawned it, and use its very existence as evidence of a more profound America’.

A year later, in an essay entitled ’What does nonviolence mean’, LeRoi Jones examines the cost of non-violence (to the Negro) and denounces ’the Liberal/ Missionary syndrome’ which sought to perpetuate it. He condemns Martin Luther King to the company of Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young and brands him as ’an agent of the middle-class power structure, black and white’. Already the anguish is breaking into bitterness. ’Four Negro children were blown to bits while they were learning to pray’ in a church in Birmingham, the leader of the Jackson branch of the NAACP was assassinated in front of his home, the murder of Medgar Evers was still unavenged, Robert Williams was framed and sent into exile-this and so much more had curled up the soul of LeRoi Jones. (The reference to the four Negro children occurs over half a dozen times in the second part of the book.) And yet he wrote: ’By not allowing a grassroots protest to issue from the core of the oppressed black masses, the American white man is forcing another kind of protest to take shape, one that will shake the whole society at its foundations, and succeed in changing it, if only into something worse.’ This is no more than the finding of the President’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders published last week, but five years on.

1964: ’I write now full of trepidation because I know the death this society intends for me. I see Jimmy Baldwin almost unable to write about himself any more. I’ve seen Du Bois, Wright, Chester Himes, driven away-Ellison silenced and fidgeting in some college…. But let them understand that this is a fight without quarter, and I am very fast.’ And in his next essay ’The last days of the American empire (including some instructions for black people)’ he finally despairs that ’the black man cannot become an American (unless we get a different set of rules) because he is black’. But ’You are strong’, he tells his people and urges them not to be separated from their brothers and sisters or from their culture. And we note how the idiom and with it the whole ethos of the Negro movement has changed from ’You are beautiful’ to ’You are strong’. And so to the three essays of 1965: ’… Black Male’, ’Black Hope’, and ’The Legacy of Malcolm X and the coming of the Black Nation’. There are no nuances of colour here, just an unrelenting black. ’The Black Man must aspire to Blackness … The Black Man must idealise himself as Black … The Black Man must seek a Black politics….’ And again: ’The solution of the Black Man’s problems will come only through Black National Consciousness.’ Finally: ’It is this that the Black Man must have, an autonomous nation, his own forms: treaties, agreements, laws.’ His disillusion is complete. To this reviewer at least, LeRoi Jones comes through as a poet so sensitive to pain, so much pain, his and his people’s, that he has lost all vision. But he does ’tell it as it is’, and it is up to those of us who are not in one sort of prison or another to take up where his eyes left off seeing; we the seers must look again through the blind blind night of his despair.