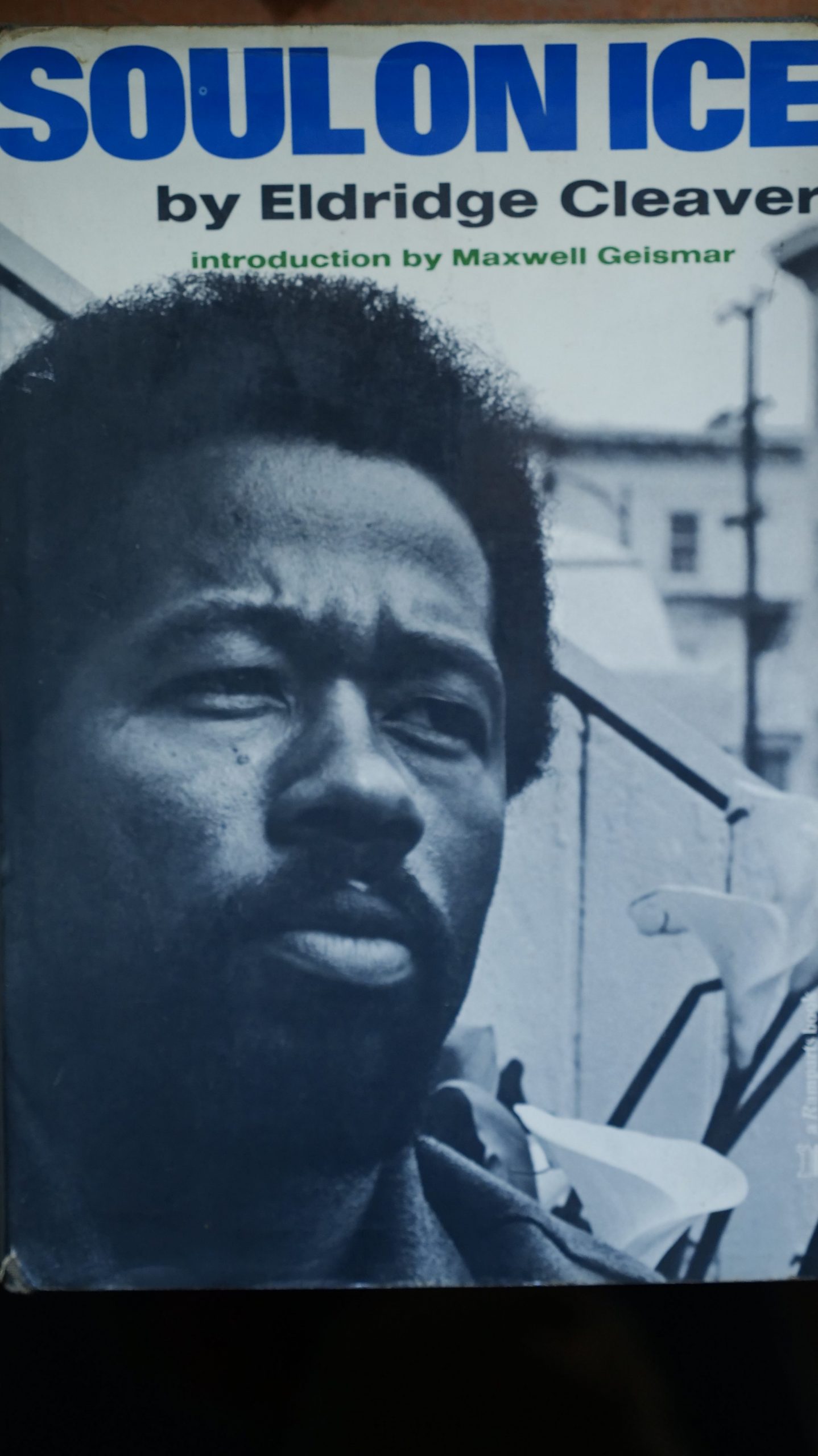

Soul on Ice. By ELDRIDGE CLEAVER (London, Jonathan Cape, 1969). xv + 210 pp. 35s.

Life is a renewal, an assertion, a continual yea-saying. It holds out no new truths, only the old ones. And these one needs to discover for oneself-anew, afresh, over and over again-in terms of one’s own experience. When, however, that experience is constituted of the bare business of staying alive, the only truth one is allowed to discover is that of hatred-hatred of oneself and for everyone else. But in that nothingness, to re-create the essence of one’s being (pace Gabriel Marcel) – that is the very celebration of life.

Cleaver’s achievement is no less than that, and it is the main achievement of Soul on Ice. There are other things too in the various essays and letters which go to make up this book, but they are incidental to, or, rather, radiate from, his initial essay ‘On Becoming’. The venue of his ‘becoming’ is Folsom Prison, where he is serving a sentence on a charge of rape. Earlier, when he was eighteen, he had been sent to Soledad State Prison for being in possession of marijuana and there he had reflected that his, as indeed every black man’s, ‘Ogre’ was the white woman, so ordained by the white man’s law. And to avenge himself on the white man he decided to violate his woman (‘rape was an insurrectionary act’), and this he proceeded to do. But, afterwards, in Folsom Prison, Cleaver takes a long look at himself and finds that he can no longer justify his action, if only because it was a departure from his own humanity. ‘I lost my self-respect’, he says. ‘My pride as a man dissolved and my whole fragile moral structure seemed to collapse .. .’ The essay ends with the realization that ‘the price of hating other human beings is loving oneself less’.

The discovery is not new, but there is a freshness about it, and a force, which evokes in us a reciprocal desire to examine afresh those values which we once had taken for granted. And it is evoked not with the art which conceals art, but with that honesty of revelation which constitutes an aspect of love.

So too, in his essay on Lovdjieff, the prison teacher, Cleaver apprises us of our failing sense of wonderment-not directly, but through his own wide-eyed wonder at Lovdjieff’s sense of wonderment-this man who could ‘weep over a line of poetry … over the fact that man can talk, read, write, walk, reproduce, die, eat, eliminate-over the fact that a chicken can lay an egg.’

Cleaver sees, too, in terms of the American scene what Buber had seen in more universal terms when he declared that ‘a society may be termed human in the measure to which its members confirm one another’. The theme under lies all Cleaver’s essays, but the one entitled ‘Lazarus, come forth’, although superficially a piece on boxing as the virility symbol of the American male, carries the message that not until ‘both Paul Bunyan and John Henry can look upon themselves and each other as men, the strength in the image of the one not being at the expense of the other’ can America reclaim itself.

But what is perhaps Cleaver’s profoundest ‘discovery’-and it is this which illumines his love letters to Beverly Axelrod, his lawyer-is the complementarity of man and woman, the realization that human duality is an antithesis eternally striving for synthesis in, what Karl Stern has called, ‘an act of anticipation and restitution of unity’. In Cleaver’s terminology: ‘when the Primeval Sphere divided itself, it established a basic tension of attraction, a dynamic magnetism of opposites-the Primeval Urge-which exerts an irresistible attraction between the male and female hemispheres, even tending to fuse them back together into a unity in which the male and female realize their true nature .. .’ But this ‘Apocalyptic Fusion’ or ‘Unitary Sexual Image’ cannot occur in a society which seats the ‘Mind’ in the ruling classes and the ‘Body’ in the classes below, resulting in the fragmentation of the ‘Self’ and therefore of the ‘Unitary Social Image’. Only in a classless society can men and women achieve their ‘supreme identity’ in and through each other. Meanwhile, a class-ridden and racist society throws up the ‘Amazon’ and the ‘Ultrafeminine’, the ponce and the pansy.

From philosophy to sociology, from eternal truths to the immediate, Cleaver’s concern is pervasive and intense. And although the sociological pieces tend to be the least original, there is one piece, ‘The Allegory of the Black Eunuchs’, which demystifies, in a matter of twenty-five pages, the ponderous sociology of Moynihan and his ilk.