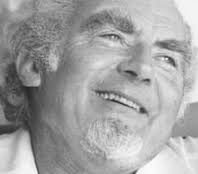

A tribute to Basil Davidson in a special issue of Race & Class ( 36/2,October 1994)

When Race & Class was breech-birthed from Race, in the palace revolution that overthrew the empire loyalists who ran the Institute of Race Relations twenty years ago, its features were still undefined and its future unformed. All that those of us who were engaged in the hard graft of bringing out the journal knew was that if, as our first editorial stated, we wanted to think in order to do and not think in order to think, then we had to get rid of the arid scholarship of an editorial board that for long had set the tone and tenor of Race. What we did not know then was how much more tenacious academics were in holding on to the privilege of privatising and rarifying knowledge than were the capitalists in holding on to power. Some of them even insisted that the appointment of the editor – who in the reconstructed Institute was to be elected by the staff – must remain in their gift. In desperation, we sacked the lot (as the blank inside cover of the April ’74 number would testify) and looked beyond academia to see who could help us harness learning to liberation. And our eyes fell on Basil Davidson and Thomas Hodgkin and Malcolm Caldwell and Ken Jordaan and, later, Eqbal Ahmad and Orlando Letelier.

Basil had already been an (uneasy) member of the old IRR, had on occasion addressed lunch-time meetings there and, in 1971, had threatened to resign from the Institute if its other journal, Race Today, continued systematically to ignore the freedom struggles in ‘Portuguese Africa’. Basil did not know it at the time, but that intervention strengthened the hand of the staff against the management in its battle to control Race Today. Subsequently, when the Institute was setting its new direction, we persuaded Basil to join the Editorial Working Committee of Race & Class.

And it was Basil, along principally with Thomas Hodgkin, that great and good man, who helped Race & Class formulate its politics and determine its principles. Through Basil, we learnt to write simply and directly, without obfuscation or high theory, with commitment and clarity. and to insist that contributors to the journal do likewise. We learnt, quite simply, that the people we were fighting for should be the people we were writing for – the liberation of Black and Third World peoples.

Basil opened us up, as he did everyone else. to the liberation struggles of Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique and Angola, and in the process provided us with two key texts from Amilcar Cabral that inform the politics of the journal to this day. First, that the culture of a people was the combusting force of their revolution and was outward-looking, dynamic, organic, not static, historicist and interiorised and, second, that theory did not exist of itself and for itself. but was a weapon in the struggle. The function of knowledge was to liberate. In the course of adhering to these principles, we learnt, too, the truth of Cabral’s other dictum: without committing class suicide, we could not serve the cause that the journal espouses in its masthead.

As we commemorate Basil’s ‘eightieth year to heaven’ we are reminded that the same battles that Basil fought and still fights so valiantly and effectively have to be fought and won all over again. For, the destiny of Third World peoples has once more moved into the hands of a new capitalist world order and intellectuals no longer speak truth to power.

We dedicate this isssue to Basil and the tasks he has set us.