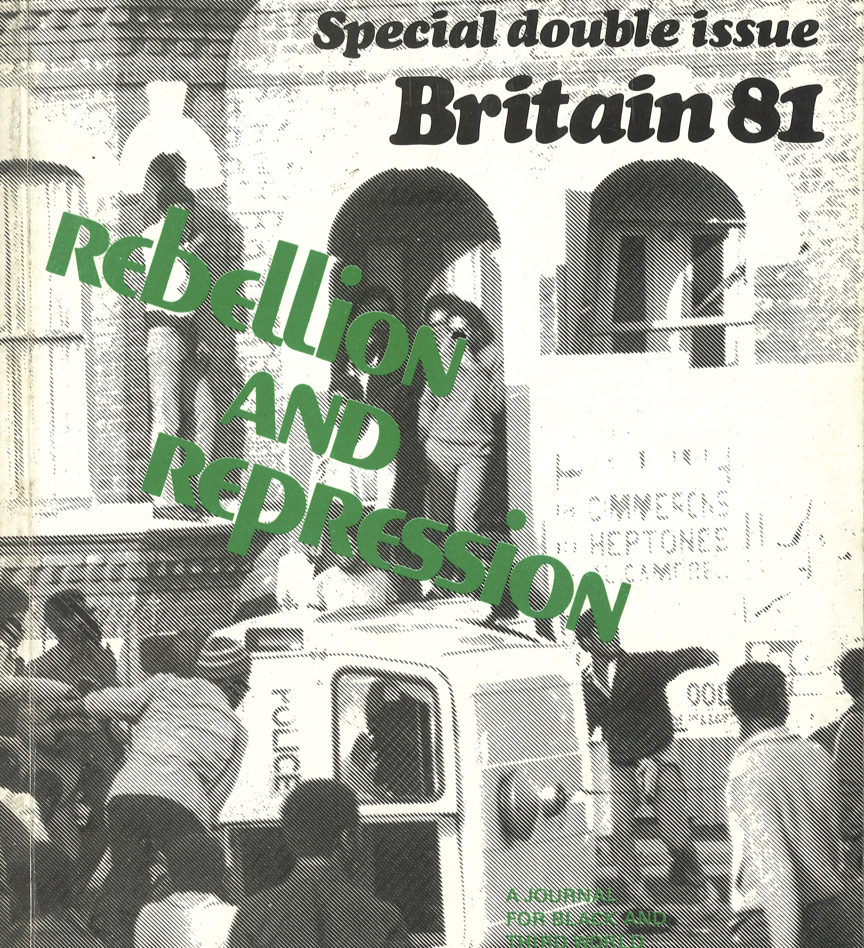

First published in ‘Rebellion and repression’, a special issue of Race & Class, 23/2&3, Autumn 1981

On 25 June 1940 Udham Singh was hanged. At a meeting of the Royal Asiatic Society and the East India Association at Caxton Hall, London, he had shot dead Sir Michael O’Dwyer, who (as the Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab) had presided over the massacre of unarmed peasants and workers at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, in 1919. Udham was a skilled electrician, an active trade unionist and a delegate to the local trades council, and, in 1938, had initiated the setting up of the first Indian Workers’ Association, in Coventry.

In October 1945 at Chorlton Town Hall in Manchester the fifth Pan-African Congress, breaking with its earlier reformism, pledged itself to fight for the ’absolute and complete independence’ of the colonies and an end to imperialism, if need be through Gandhian methods of passive resistance. Among the delegates then resident in Britain were Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, George Padmore, Wallace- Johnson, C.L.R. James and Ras Makonnen. W.E.B. DuBois, who had founded the Pan-African Congress in America in 1917, presided.

In September 1975 three young West Indians held up a Knightsbridge restaurant for the money that would help set up proper schools for the black community, finance black political groups and assist the liberation struggles in Africa.

Of such strands have black struggles in Britain been woven. But their pattern was set on the loom of British racism.

In the early period of post-war reconstruction, when Britain, like all European powers, was desperate for labour, racialism operated on a free market basis – adjusting itself to the ordinary laws of supply and demand. So that in the sphere of employment, where too many jobs were seeking too few workers – as the state itself had acknowledged in the Nationality Act of 1948 – racialism did not debar black people from work per se. It operated instead to deskill them, to keep their wages down and to segregate them in the dirty, ill-paid jobs that white workers did not want – not on the basis of an avowed racialism, but in the habit of an acceptable exploitation.In the sphere of housing,where too many people were seeking too few houses, racialism operated more directly to keep blacks out of the housing market and to herd them into bed-sitters in decaying inner city areas. And here the racialism was more overt and sanctioned by society. ’For the selection of tenants’, wrote Ruth Glass scathingly, is regarded as being subject solely to the personal discretion of the landlord. It is understood that it is his privilege to bar Negroes,

Sikhs, Jews, foreigners in general, cockneys, socialists, dogs or any other species which he wants to keep away. The recruitment of workers, however, in both state and private enterprises is a question of public policy – determined explicitly or implicitly by agreements between trade unions, employers’ associations and government. As a landlord, Mr. Smith can practise discrimination openly; as an employer, he must at least disguise it. In the sphere of housing, tolerance is a matter of private initiative; in the sphere of employment, it is in some respects ‘nationalised’.

That same racialism operated under the twee name of colour bar in the pubs and clubs and bars and dance-halls to keep black people out. In schooling there were too few black children to cause a problem: the immigrants, predominantly male and single, had not come to settle. The message that was generally percolating through to the children of the mother country was that it was their labour that was wanted, not their presence. Racialism, it would appear, could reconcile that con- tradition on its own – without state interference, laissez-faire, drawing on the traditions of Britain’s slave and colonial centuries.

The black response was halting at first. Both Afro-Caribbeans and Asians, each in their own way, found it difficult to come to terms with such primitive prejudice and to deal with such fine hypocrisy. The West Indians, who, by and large, came from a working-class background they were mostly skilled craftsmen at this time -found it particularly difficult to accept their debarment from pubs and clubs and dance-halls (or to put up with the plangent racialism of the churches and/or their congregations). Fights broke out -and inevitably the police took the side of the whites. Gradually the West Indians began to set up their own clubs and churches and welfare associations – or met in barber’s shops and cafes and on street corners, as they were wont to do back home. The Indians and Pakistanis, on the other hand, were mostly rural folk and found their social life more readily in their temples and mosques and cultural associations. Besides, it was through these and the help of elders that the non-English speaking Asian workers could find jobs and accommodation, get their official forms filled in, locate their kinsmen or find their way around town.

In the area of work, too, resistance to racialism took the form of ad hoc responses to specific situations grounded in tradition. Often those responses were individualistic and uncoordinated, especially as between the communities -since Asians were generally employed in factories, foundries and textile mills, while recruitment of Afro- Caribbeans was concentrated in the service industries (transport, health and hotels). And even among these, there were ’ethnic jobs’, like in the Bradford textile industry, and, often, ’ethnic shifts’.

A racial division of labour (continued more from Britain’s colonial past than inaugurated in post-war Britain) kept the Asian and Afro- Caribbean workers apart and provided little ground for common struggle. Besides, the black workforce at this time, though concentrated in certain labour processes and areas of work, was not in absolute terms a large one – with West Indians outnumbering Indians and Pakistanis. Hence, the resistance to racial abuse and discrimination on the shop floor was more spontaneous than organised – but both individual and collective. Some workers left their jobs and went and found other work. Others just downed tools and walked away. On one occasion a Jamaican driver, incensed by the racialism around him, just left his bus in the High Street and walked off. (It was a tradition that reached back to his slave ancestry and would reach forward to his children.) But there were also efforts at collective action on the factory floor. Often these took the form of petitions and appeals regarding working conditions, facilities, even wages – but, unsupported by their white fellows, they had little effect. On occasions, there were attempts to form associations, if not unions, on the shop floor. In 1951, for instance, skilled West Indians in an ordnance factory in Merseyside (Liverpool) met secretly in the lavatories and wash rooms to form a West Indian association which would take up cases of discrimination. But the employers soon found out and they were driven to hold their meetings in a neighbouring barber’s shop – from which point the association became more community oriented. Similarly, in 1953 Indian workers in Coventry formed an association and named it, in the memory of Udham Singh, the Indian Workers’ Association. But these early organisations generally ended up as social and welfare associations. The Merseyside West Indian Association, for instance, went through a period of vigorous political activity – taking up cases of discrimination and the cause of colonial freedom – but even as it grew in numbers and out of its barber’s shop premises and into the white-run Stanley House, it faded into inter-racial social activity and oblivion.

Discrimination in housing met with a community response from the outset: it was not, after all,a problem that was susceptible to individual solutions. Denied decent housing (or sometimes any housing at all), both Asians and Afro-Caribbeans took to pooling their savings till they were sizeable enough to purchase property. The Asians operated through an extended family system or ’mortgage clubs’ and bought short-lease properties which they would rent to their kinsfolk and countrymen. Similarly, the West Indians operated a ’pardner’ (Jamaican) or ’sou-sou’ (Trinidadian) system, whereby a group of people (invariably from the same parish or island) would pool their savings and lend out a lump sum to each individual in turn. Thus their savings circulated among their own communities and did not go into banks or building societies to be lent out to white folk.

It was a sort of primitive banking system engendered by tradition and enforced by racial discrimination. Of course, the prices the immigrants had to pay for the houses and the interest rates charged by the sources that were prepared to lend to them forced them into overcrowding and multi-occupation, invoking not only further racial stereotyping but, in later years, the rigours of the Public Health Act.

Thus it was around housing principally, but through traditional cultural and welfare associations and groups, that black self-organisation and self-reliance grew, unifying the respective communities. It was a strength that was to stand them in good stead in the struggles to come.

There was another area, too, where such organisation was significant – and offered up a different unity: the area of anti-colonial struggle. There had always been overseas students’ associations – African, Asian, Caribbean – but in the period before the First World War these were mostly in the nature of friendship councils, social clubs or debating unions. But after that war and with the ‘race riots’ of 1919 (in Liverpool, London, Cardiff, Hull and other port areas where West African and lascar seamen had earlier settled) still fresh in their mind, West African students formed the West African Students’ Union in 1925, with the explicit aim of opposing race prejudice and colonialism. It was followed in 1931 by the predominantly West Indian League of Coloured Peoples. This was headed by an ardent Christian, Dr Harold Moody, and devoted to ’the welfare of coloured peoples in all parts of the world’ and to ’the improvement of relations between the races’.

But its journal, Keys, investigated and exposed cases of racial discrimijnation and in 1935, when ’colonial seamen and their families’, especially in Cardiff, were being subjected to great economic hardship because of their colour, indicted ‘the Trade Union, the Police and the Shipowners’ of ’cooperating smoothly in barring coloured Colonial Seamen from signing on ships in Cardiff’.

The connections – between colonialism and racialism, between black students and black workers – were becoming clearer, the campaigns more coordinated. And to this was added militancy when in 1937 a group of black writers and activists – including C.L.R. James, Wallace-Johnson, George Padmore, Jomo Kenyatta and Ras Makonnen – got together to form the International African Service Bureau. In 1944 the Bureau merged into the Pan-African Federation to become the British section of the Pan-African Congress Movement. From the outset, the Bureau (and then the Federation) was uncompromising in its demand for ’democratic rights, civil liberties and self- determination’ for all subject peoples.

As the Second World War drew to a close and India’s fight for swaraj stepped up, the movement for colonial freedom gathered momentum. Early in 1945 Asians, Africans and West Indians then living in Britain came together in a Subject Peoples’ Conference. Already in February that year, the Pan-African Federation, taking advantage of the presence of colonial delegates at the World Trade Union Conference, had invited them to a meeting at which the idea of another Pan-African Congress was mooted. Accordingly, in October 1945 the Fifth Pan-African Congress met in Manchester and, inspired by the Indian struggle for independence, forswore all ’gradualist aspirations’ and pledged itself to ’the liquidation of colonialism and imperialism’. Nkrumah, Kenyatta, Padmore, James – they were names that were to crop up again (and again) in the history of anti-racist and anti- imperialist struggle.

Three years later India was free and the colonies of Africa and the Caribbean in ferment. By now, there was hardly an Afro-Caribbean association in Britain which did not espouse the cause of colonial independence and of black struggle generally. Asian immigrants, however, were past independence (so to speak) and the various Indian Leagues and Workers’ Associations which had earlier taken up the cause of swaraj had wound down. In their place rose Indian Workers’ Associations (the name was a commemoration of the past) concerned with immigrant issues and problems in Britain, though still identifying with political parties back home, the Communist Party and Congress in particular. So that two broad strands begin to emerge in IWA politics: one stressing social and welfare work and the other trade union and political activity – though not exclusively so.

In sum, the anti-racial and anti-colonial struggle of this period was beginning to break down island and ethnic affiliations and associations and to re-form them in terms of the immediate realities of social and racial relations, engendering in the process strong community bases for the shop floor battles to come. But different interests predicated different unities and a differential racialism engendered different though similar organisational impulses. There was no one unity – or two or three – but a mosaic of unities. However, as the colonies began to be free and the immigrants to become settled and the state to sanction and institute racial discrimination, and thereby provide the breeding ground for fascism, the mosaic of unities and organisations would resolve itself into a more holistic, albeit shifting, pattern of black unity and black struggle.

By 1955 the first ’wave’ of immigration had begun to taper off: a mild recession had set in and the demand for labour had begun to drop (though London Transport was still recruiting skilled labour from Barbados in 1956). Left to itself, immigration from the West Indies was merely following the demand for labour; immigration from the Indian subcontinent, especially after the restrictions placed on it by the Indian and Pakistani governments in 1955, was now more sluggish. But racialism was hotting up and there were calls for immigration control, not least in the House of Commons. There had always been the occasional ’call’, more for political reasons than economic; now the economy provided the excuse for politics. Pressure was also building up on the right. The loss of India and the impending loss of the Caribbean and Africa had spelt the end of empire and the decline of Britain as a great power. All that was left of the colonial enterprise was the ideology of racial superiority; it was something to fall back on. Mosley’s pre-war British Union of Fascists was now revived as the Union Movement and was matched for race hatred by a rash of other organisations: A.K. Chesterton’s League of Empire Loyalists, Colin Jordan’s White Defence League, John Bean’s National Labour Party, Andrew Fountaine’s British National Party. And in the twilight area, between these and the right wing of the Tory Party, various societies for ’racial preservation’ were beginning to sprout. Racial attacks became a regular part of immigrant life in Britain. More serious clashes occurred intermittently in London and several provincial cities. And in 1954, ’in a small street of terraced houses in Camden Town [London], racial warfare was waged for two days’, culminating in a petrol bomb attack on the house of a West Indian. Finally, in August 1958 large-scale riots broke out in Nottingham and were soon followed in Notting Hill (London), where Teddy-boys, directed by the Mosleyites and the White Defence League, had for weeks gone on a jamboree of ’nigger-hunting’ under the watchful eye of the police.

The blacks struck back, and even moderate organisations like the Committee of African Organisations, having failed to obtain ’adequate unbiased police protection’, pledged to organise their own defence. The courts, in the person of a Jewish judge, Lord Justice Salmon, made amends by sending down nine Teddy-boys and establishing the right of ‘everyone, irrespective of the colour of their skin … to walk through our streets with their heads erect and free from fear’. He also noted that the Teddy-boys’ actions had ‘filled the whole nation with horror, indignation and disgust’. It was to prove the last time when such a claim could be made on behalf of the nation. Less than a year later a West Indian carpenter, Kelso Cochrane, was stabbed to death on the streets of Notting Hill. The police failed to find the killer. It was to prove the first of many such failures.

The stage was set for immigration control. But the economy was beginning to recover and the Treasury was known to be anxious about the prospect of losing a beneficial supply of extra labour for an economy in a state of expansion – though the on-going negotiations for entry into the EEC promised another supply. Besides, the West Indian colonies were about to gain independence and moves towards immigration control, it was felt, should be postponed till after the British plan for a West Indian Federation had been safely established. Attempts to interest West Indian governments in a bilateral agreement to control immigration failed. In 1960 India withdrew its restrictions on emigration. In 1961 Jamaica withdrew its consent to a Federation. In early 1962 the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill was presented to parliament.

If the racial violence of Nottingham and Notting Hill had impressed on the West Indian community the need for greater organisation and militancy, the moves to impose ’coloured’ immigration control strengthened the liaison between Asian and West Indian organisations. Already, in 1957, Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian and a Communist, who had been imprisoned for her political activities in the US and then deported, had canvassed the idea of a campaigning paper. In March1958 she, together with other West Indian progressives – Amy Garvey (the widow of Marcus Garvey) among them – brought out the first issue of what was to prove the parent Afro-Caribbean journal in Britain,* the West Indian Gazette. In 1959, after the Kelso Cochrane kill- ing, Claudia Jones and Frances Ezzrecco (who had founded, in the teeth of the riots, the Coloured Peoples Progressive Association) led a deputation of West Indian organisations to the Home Secretary.

*From its loins was to spring Link, Carib, Anglo-Caribbean News, Tropic, Flamingo, Daylight International, West Indies Observer, Magnet and others.

And in the same year, ‘to get the taste of Notting Hill out of their throats’, the West Indian Gazette launched the first Caribbean carnival in St Pancras Town Hall.

At about the same time, at the instance of the High Commission of the embryonic West Indian Federation (Norman Manley, Chief Minister of Jamaica, had flown to London after the troubles), the more moderate Standing Conference of West Indian Organisations in UK was set up. Although its stress was on integration and multi- racialism, it helped to cohere the island groups into a West Indian entity.

Nor had the Asian community been unmoved by the 1958 riots, for soon afterwards an Indian Association was formed in Nottingham and, more significantly, all the local IWAs got together to establish a central IWA-GB. (Nehru had advised it on his visit to London a year earlier.)

Now, with immigration control in the offing, other organisations began to develop – among them the Pakistani Workers’ Association (1961) and the West Indian Workers’ Association (1961). And these, along with a number of other Asian and Afro-Caribbean organisations, combined with sympathetic white groups to campaign against discriminatory legislation. The two most important umbrella organisations were the Co-ordinating Committee Against Racial Discrimination (CCARD) in Birmingham and the Conference of Afro-Asian- Caribbean Organisations (CAACO) inLondon. The former was set up in February 1962 by Jagmohan Joshi, of the IWA Birmingham, and Maurice Ludmer, an anti-fascist crusader from way back and later the founder-editor of Searchlight. CCARD itself had been inspired by a meeting at Digbeth called by the West Indian Workers’ Association and the Indian Youth League to protest Patrice Lumumba’s murder. That meeting had led to a march through Birmingham and other meetings against imperialism. In September 1961 CCARD led a contingent of blacks and whites through the streets of Birmingham in a demonstration against the Immigration Bill.

CAACO, initiated by the West Indian Gazette and working closely with the IWA and Fenner Brockway’s Movement for Colonial Freedom, had its meetings and marches too, but it concentrated more on lobbying the High Commissions and parliament, particularly the Labour Party which had pledged to repeal the Act (if returned to power). But in August 1963, after the Bill had become Act and the Labour Party, with an eye to the elections, had begun to sidle out of its commitment, CAACO (with Claudia Jones at its head) organised a solidarity march from Notting Hill to the US embassy in support of ’negro rights’ in the US and against racial discrimination in Britain – three days after Martin Luther King’s Peoples’ March on Washington. But international events also had adverse effects on black domestic politics. The Indo-China war in 1962 had split the Communist parties in India. It now engendered schisms in the IWA-GB.

In April 1962 the Bill was passed and the battle lost. Racialism was no longer a matter of free enterprise; it was nationalised. If labour from the ’coloured’ Commonwealth and colonies was still needed, its intake and deployment was going to be regulated not by the market forces of discrimination but by the regulatory instruments of the state itself. The state was going to say at the very port of entry (or non-entry) which blacks could come and which blacks couldn’t – and where they could go and where they could live – and how they should behave and deport themselves. Or else … There was the immigration officer at the gate and the fascist within: racism was respectable, sanctioned, but with reason, of course; it was not the colour, it was the numbers – and for the immigrants’ sakes – for fewer blacks would make for better race relations – and that, surely, must improve the immigrants’ lot. It was a theme that was shortly to be honed to a fine respectability by Hat- tersley* and the Labour government. Evidently, hypocrisy too had to be nationalised. And in pursuit of that earnest, the Labour government of 1964 would make gestures towards anti-discriminatory legislation.**

*Without integration, limitation is inexcusable; without limitation, integration is impossible.’ (Roy Hattersley, MP, 1965)

**That Fenner Brockway, a ceaseless campaigner for colonial freedom, had introduced a Private Member’s anti-discrimination bill year after year after year from 1951 had, of course, made no impact on Labour consciousness.

Meanwhile, the genteel English ‘let it all hang out’. In April 1963 the Bristol Omnibus Company discovered that it did not ’employ a mixed labour force as bus crews’ -and freed from shame by the new absolution, it announced fearlessly ’a company may gain say fifteen coloured people and lose, through prejudice, thirty white people who decide they would sooner not work with them’ . But if Bristol – with three generations of black settlers and built on slavery – was only weighing up the statistics of prejudice, Walsall (with its more recent experience of blacks) made the more scientific pronouncement that ‘coloureds can’t react fast in traffic’. Bolton simply refused to engage ‘riff-raff’ any longer.

The police felt liberated too. They had in the past appeared to derive only a vicarious pleasure from attacks on blacks; they had to be seen to be neutral. Now they themselves could go ‘nigger-hunting’ -the phrase was theirs – while officially polishing up on their neutrality. In December 1963 the British West Indian Association complained of in- creasing ’police brutality’ stemming from the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act. In 1964 the Pakistani community alleged that the wrists of Pakistani immigrants were being stamped with indelible ink at a police station in the course of a murder investigation: it was irrelevant that they had names and, besides, they all looked alike. In 1968 the West Indian Standing Conference (which replaced the more moderate Standing Conference of West Indian Organisations in UK after the fall of the West Indian Federation in 1962) documented police excesses in Brixton and surrounding areas in a report on Nigger-hunting in England. And at the ports of entry immigration officers, given carte-blanche in the ’instructions’ handed down by the government, were having a field day.

At the local level, tenants’ and residents’ associations were organising to keep blacks out of housing. The number of immigrants had increased considerably in the two years preceding the ban: they were anxious to bring in their families and dependants before the doors finally closed. Housing, which had always been a problem since the war, became a more fiercely contested terrain. The immigrants had, of course, been consigned to slum houses and forced into multi- occupation. Now there were fears that they would move further afield into the white residential areas. At the same time, public health laws were invoked to dispel multi-occupation.

Schooling, too, presented a problem, as more and more coloured children began to enter the country and sought places in their local schools. In October 1963 white parents in Southall (which had a high proportion of Indians) demanded separate classes for their children because coloured children were holding back their progress. In December the Commonwealth Immigrants’ Advisory Council(CIAC),which had been set up to advise the HomeSecretary on matters relating to ’the welfare and integration of immigrants’, reported that ’the presence of a high proportion of immigrant children in one class slows down the general routine of working and hampers the progress of the whole class, especially where the immigrants do not speak or write English fluently’. This, it said, was bad for immigrant children too – for ’they would not get as good an introduction to British life as they would get in a normal school’. Besides, there was the danger of white parents removing their children and making some schools ’predominantly immigrant schools’. In November Sir Edward Boyle, the avowedly liberal Minister of Education, told the House of Commons that it was ’desirable on education grounds that no one school should have more than about 30% of immigrants’. Accordingly, in June 1965 Boyle’s law enacted that there should be no more than a third of immigrant children in any school; the surplus should be bussed out’ – but white children would not be bussed in.

As for West Indian children, whose difficulties were ostensibly. ’Creolese English’, low educability and ‘behaviour problems’, the solution would be found in ’remedial classes’ and even ’special’ schools. None of these measures – or the various instances of discrimination – went without protest, however. The Bristol Bus Company, for in- stance, was subjected to a boycott and demonstrations for weeks until it finally capitulated. Police harassment, as already mentioned, was documented and publicised by West Indian organisations. The relegation of West Indian children into special classes and/or schools was fought-and continued to be fought-first by the North London West Indian Association and then by other local and national organisations.

But, by and large, the unity – between West Indians and Asians, militants and moderates – that had sprung up between the riots of 1958 and the Immigration Act of 1962 had been dissipated by more immediate concerns. Now there were families to house and children to school and dependants to look after: the immigrants were becoming settlers. And since it was Asian immigrants who, more than the West Indian, had come on a temporary basis – to make enough money to send to their impoverished homes – before the Immigration Act fore- closed on them, it was their families and relatives who swelled the numbers now. And their politics tended to become settler politics – petitioning, lobbying, influencing political parties, weighing-in on (if

not yet entering) local government elections – and their struggles working-class struggles on the factory floor – and they, by virtue of being fought in the teeth of trade union racism, were to prove political too.

In May 1965 the first important ’immigrant’ strike took place – at Courtauld’s Red Scar Mill in Preston – over the management’s decision to force Asian workers (who were concentrated, with a few West Indians, in one area of the labour process) to work more machines for (proportionately) less pay. The strike failed, but not before it had exposed the active collaboration of the white workers and the union with management. A few months earlier, a smaller strike of Asian workers at Rockware Glass in Southall (London) had exposed a similar complicity. And the Woolf Rubber Company strike later in the same year, though fought valiantly by the workers, supported by the Asian community and in particular by the IWA, lost out to the employers through lack of official union backing.

The Afro-Caribbean struggles of this period (post 1962) also reflected a similar community base, though different in origins. Ghana had become free in 1957, Uganda in 1962 and Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago in the same year, but there were other black colonies in Africa and the Caribbean still to be liberated. And then there was the black colony in North America, which, beginning with Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement, was revving up into the Black Power struggles of the mid-1960s. King visited London on the way to receiving his Nobel prize in Oslo in December 1964. And at his instigation, a British civil rights organisation, the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) was formed in February 1965 – federating various Asian and Afro- Caribbean organisations and sporting Labour Party ’radicals’.

More significant, however, was the visit of Malcolm X. Malcolm blitzed London in February 1965 and in his wake was formed a much more militant organisation, the Racial Action Adjustment Society (RAAS)*, with Michael de Freitas, later Abdul Malik and later still Michael X, at its head. ’Black men, unite,’ it called, ’we have nothing to lose but our fears.’ It is the fashion today, even among blacks, to see Michael X only as a criminal who was justifiably hanged for murder by the Trinidadian government (1975). (The line between politics and crime, after all, is a thin one -in a capitalist society.) But it was Michael and Roy Sawh (’Guyanese Indian’) and their colleagues in RAAS who,as we shall see, more than any body else in this period freed ordinary black people from fear and taught them to stand up for their rights and their dignity.** It was out of the RAAS stable, too, that a number of our present-day militants have emerged.

*Raas, a Jamaican swear word, gave a West Indian flavour to Black Power.

**I remember the time in South London when an old black woman was being jostled and pushed out of a bus queue. Michael went up and stood behind her, an ill-concealed machete in his hand – and the line of lily-white queuers vanished before her – and she entered the bus like royalty.

It is also alleged, in hindsight and contumely, that RAAS had no politics but the politics of thuggery. But it was RAAS who descended on Red Scar Mills in Preston to help the Asian strikers (at their invitation). And the point is telling – if only because it marked a progression in the organic unity of the (Afro-) Asian ’coolie’ and (Afro-) Caribbean, slave, struggles in the diaspora, begun in Britain by Claudia Jones’ West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asia-Caribbean News on which Abimanyu Manchanda, an Indian political activist and a key figure in the British anti-Vietnam war movement, was to work.

But RAAS, or black militancy generally, would not have had the backing it did but for the growing disillusion with the Labour Party’s policies on immigration control and, therefore, racism. The ’coloured immigrants’ still had hopes in the party of the working class and of colonial independence and sought to influence its policies. But after the 1964 general election, Labour’s position became clearer. Peter Griffiths, the Tory candidate for Smethwick (an ’immigrant area’ in Birmingham), had campaigned on the basis of ending immigration and repatriating ’the coloureds’.

If you want a nigger neighbour, Vote Labour’ he had sloganised-and won. But Labour won the election and Harold Wilson the incoming Prime Minister, denounced Griffiths as ’a parliamentary leper’. However, Wilson’s policies were soon to become leprous too: the Immigration Act was not only renewed in the White Paper of August 1965 but went on to restrict ’coloured immigration’ further on the basis that fewer numbers made for better race relations. In pursuit of that philosophy, Labour then proceeded to pass a Race Relations Act (September 1965), which threatened racial discrimination in ’places of public resort’ with conciliation. It was prepared, however, to penalise ’incitement to racial hatred’ – and promptly proceeded to prosecute Michael X.

Equally off-target and ineffectual were the two statutory bodies that Labour set up, the National Committee for Commonwealth Immigrants(NCCI) and the Race Relations Board(RRB) -the one chiefly to liaise with immigrants and ease them out of the difficulties (linguistic, educational, cultural and so on) which prevented integration, and the other, as mentioned above, to conciliate discrimination in hotels and places through conciliation committees.

To ordinary blacks these structures were irrelevant: liaison and conciliation seemed to define them as a people apart who somehow needed to be fitted into the mainstream of British society – when all they were seeking were the same rights as other citizens. They (liaison and conciliation) were themes that were to rise again in the area of police-black relations – this time as substitutes for police accountability – and not without the same significance.

But if NCCI failed to integrate the ’immigrants’, it succeeded in disintegrating ’immigrant’ organisations – the moderate ones anyway and local ones mostly – by entering their areas of work, enticing local leaders to cooperate with them (and therefore government) and pre-empting their constituencies. Its greatest achievement was to lure the leading lights of CARD into working with it, thereby deepening the contradictions in CARD (as between the militants and the moderates). WISC and NFPA* disaffiliated from CARD and the more militant blacks followed suit, leaving CARD to its more liberal designs. The government had effectively shut out one area of representative black opinion. But an obstacle in the way of the next Immigration Act had been cleared.

When CARD finally broke up in 1967 the press and the media generally welcomed its debacle. They saw its sometimes uncompromising stand against racial discrimination as a threat to ’integration’ (if not to white society), resented its outspoken and articulate black spokes-men and women, denouncing them as Communists and Maoists, and feared that it would emerge from a civil rights organisation into a Black Power movement. The ’paper of the top people’, having warned the nation of ’The Dark Million’ in a series of articles in the months preceding the August 1965 White Paper, now wrote, ’there are always heavy dangers in riding tigers – and these dangers are not reduced when the animal changes to a black panther’ (The Times, 9 November 1967). And a Times news team was later to write that ’the ominous lesson of CARD … is that the mixture of pro-Chinese communism and American-style Black Power on the immigrant scene can be devastating’ (International events were beginning to cast their shadows.)

The race relations pundits added their bit. The Institute of Race Relations (some of whose Council members and staff were implicated in CARD politics) commissioned a book giving the liberal version. Although an independent research organisation, replete with academics, the IRR had already been moving closer to government policies on immigration and integration – backing them with ’objective’ findings and research.

The race scene was changing – radically. The Immigration Acts, whatever their racialist promptings, had stemmed from an economic rationale, fashioned in the matrix of colonial-capitalist practices and beliefs. They served, as we have seen, to take racial discrimination out of the market-place and institutionalise it – inhere it in the structures of the state, locally and nationally. So that at both local and national levels ’race’ became an area of contestation for power. It was the basis on which local issues of schooling and housing and jobs were being, if not fought, side-tracked. It was an issue on which elections were won and lost. It was an issue which betrayed the trade unions’ claims to represent the whole of the working class, and so betrayed the class. It had entered the arena of politics (not that, subliminally, it was not always there) and swelled into an ideology of racism to be borrowed by the courts in their decision-making and by the fascists for their regeneration. *

*In real life and real struggle, the economic, the political and the ideological move in concert, with sometimes one and sometimes the other striking the dominant note — but orchestrated, always, by the mode of production. It is only the Marxist textualists who are preoccupied with ‘determinisms’, economic or otherwise.

Racial attacks had already begun to mount. In 1965, in the months preceding the White Paper but after Griffiths’ victory, ‘a Jamaican was shot and killed … in Islington, a West Indian schoolboy in Notting Hill was nearly killed by white teenagers armed with iron bars, axes and bottles … a group of black men outside a cafe in Notting Hill received blasts from a shot-gun fired from a moving car’, hate leaflets appeared in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, crosses were burnt outside ’coloured citizens’ homes’ in Leamington Spa, Rugby, Coventry, Ilford, Plaistow and Cricklewood and ’a written warning (allegedly) from the Deputy Wizard of Ku Klux Klan was sent to the Indian Secretary of CARD. ‘You will be burnt alive if you do not leave England by August’. The British fascists, however, denied any connection with the KKK – not, it would appear, on a basis of fact, but in the conviction that there was now a sufficient ground-swell of grassroots racism to float an electoral party. Electoral politics, of course, were not going to bring them parliamentary power, but they would provide a vehicle for propaganda and a venue for recruitment – and all within the law. They could push their vile cause to the limits of the law, within the framework of the law, forcing the law itself to become more repressive of democratic freedoms. By invoking their democratic right to freedom of speech, of association, etc. – by claiming equal TV time as the other electoral parties and by gaining ’legitimate’ access to the press and radio – they would propagate the cause of denying others those freedoms and legitimacies, the blacks in the first place. They would move the whole debate on race to the right and force incoming governments to further racist legislation-on pain of electoral defeat. And so, in February 1967 the League of Empire Loyalists, the British National Party and local groups of the Racial Preservation Society merged to form the National Front (NF) – and in April that year put up candidates for the Greater London Council elections.

But they – and the government – reckoned without the blacks. The time was long gone when black people, with an eye to returning home, would put up with repression: they were settlers now. And state racism had pushed them into higher and more militant forms of resistance – incorporating the resistances of the previous period and embracing both shop floor and community, Asians and Afro-Caribbeans, sometimes in different areas of struggle, sometimes together.

RAAS, as we have seen, was formed in 1965. It was wholly an indigenous movement arising out of the opposition to native British racism but catalysed by Malcolm X and the Black Muslims. And so it took in, on both counts, the African, Asian, Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American dimensions of struggle and the struggles in the work- place and the community. It had, almost as its first act, descended on the Red Scar Mills in Preston to help the Asian strikers. It then set up office in a barber’s shop in Reading and worked and recruited in the North and the Midlands with Abdulla Patel (one of the strikers from Red Scar Mills) and Roy Sawh as its organisers there. In London, too, RAAS gathered a sizeable following through its work with London busmen and its legal service (Defence) for black people in trouble with the police. It was written up in the press, often as a novel and passing phenomenon,* and appeared (in a bad light) on BBC’s Panorama programme. The disillusion with CARD swelled its numbers. And the indictment of Michael X in 1967 for ’an inflammatory speech against white people’ – when white people indulged freely in racist abuse – served to validate RAAS’s rhetoric. At Speakers’ Corner Roy Sawh and other black speakers would inveigh against ’the white devil’ and ’the Anglo-Saxon swine’, and find a ready and appreciative audience.

*With the notable exception of an article in the Observer (4 July 1965) by Colin McGlashan – but he was a rare and truthful reporter.

In June 1967 the Universal Coloured Peoples’ Association (UCPA) was formed, headed by a Nigerian playwright, Obi Egbuna. It too arose from British conditions, but, continuing in the tradition of the struggle against British colonialism, stressed the need to fight both imperialism and racism. The anti-white struggle was also anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist – universal to all coloured peoples. And so its concerns extended from racism in Britain and elsewhere to the war in Vietnam, the independence of Zimbabwe, the liberation of ’Portuguese Africa’, the cultural revolution in China. It was, of course, inspired and influenced by the Black Power struggle in America and, more immediately, by Stokely Carmichael’s visit to London in July that year.

’Black Power’, Egbuna declared at a Vietnam protest rally in Trafalgar Square in October 1967, ’means simply that the blacks of this world are out to liquidate capitalist oppression of black people wherever it exists by any means necessary.’Black people in Britain , the UCPA pointed out, though numerically small, were so concentrated in vital areas of industry, hospital services (a majority of doctors and nurses in the conurbations were black) and transport that a black strike could paralyse the economy. Some UCPA speakers at meetings in Hyde Park urged more direct action. Roy Sawh (the members of one organisation were often members of another) ’urged coloured nurses to give wrong injections to patients, coloured bus crews not to take the fares of black people … [and] Indian restaurant owners to ‘put something in the curry’. Alex Watson, a Jamaican machine- operator, it was alleged, exhorted coloured people to destroy the whites. Ajoy Ghose, an unemployed Indian, pointed out that to kill whites was not murder and Uyornumu Ezekiel, a Nigerian electrician, having derided the prime minister as a ’political prostitute’, said that England was ’going down the toilet’; They were all prosecuted; Ezekiel was discharged, the others fined.

But UCPA rhetoric was helping to stiffen black backs, its meetings and study groups to raise black consciousness, its ideology to politicise black people. The prosecution of its members showed up the complicity of the courts – ’protection rackets for the police’, the secretary of WISC was to call them. And its example, like that of RAAS, encouraged other black organisations to greater militancy.

RAAS, it would appear, stressed black nationalism, while the UCPA emphasised the struggles of the international working class. But they were in fact different approaches to the same goals. RAAS’s ‘nationalism’ stemming as it did from the West Indian experience, combined an understanding of how colonialism had divided the Asian and African and Caribbean peoples (coolie, savage and slave) with an awareness of how that same colonialism made them one people now: they were all blacks. Hence the Black House (and the cultural groups) that RAAS was briefly to set up in 1970 did not, like Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka’s Spirit House, by which it was probably inspired, exclude other ’coloureds’; the historical experience was different.

Meanwhile, the number of black strikes – mainly Asian, because it was they who were employed in the menial jobs in the foundries, the textile and paper mills, the rubber and plastic works – began to mount, and nearly all of them showed up trade union racism. Working conditions in the foundries were particularly unendurable. The job itself involved working with molten metal at 1400 degrees centigrade. Burns and injuries were frequent. The wage was rarely more than £14 a week and promotion to skilled white-only jobs was unthinkable. Every action on the part of the Asian workers was either unsupported or opposed by the trade union to which they belonged, for example in the strike at Coneygre Foundry (Tipton) in April 1967 and again in October 1968, at the Midland Motor Cylinder Co in the same year and at Newby Foundry (West Bromwich) a year later. But the support from their communities and community organisations was unwavering. The temples gave free food to strikers, the grocers limitless credit, the landlords waived the rent. And joining in the strike action were local organisations and associations – IWAs and Pakistani Welfare Associations and/or other black organisations or individuals connected with them.

Some issues, however, embraced the whole community more directly. For, apart from the general question of wages, conditions of work, etc., quite a few of these strikes also involved ’cultural’ questions, such as the right to take time off for religious festivals, the right to break off for daily prayer (among Moslems), the right of Sikh busmen to wear turbans instead of the official head-gear. And because of trade union opposition to such ’practices’, the struggles of the class and the struggles of the community, of race, became indistinguishable.

These in turn were linked to the struggles back ’home’ in the sub-continent – if only through family obligations arising from economic need predicated by under-development caused by imperialism. The connections were immediate, palpable, personal. Imperialism was not a thing apart, a theoretical concept; it was a lived experience – only one remove from the experience of racism itself. And for that reason, too, the politics and political organisations of the ’home’ countries had a bearing on the life and politics of Indian and Pakistani settlers in Britain – but now, in view of the mounting (though different) authoritarianisms in both India and Pakistan (East and West), not in terms of electoral political parties so much as in terms of the resistance movements to the authoritarian state* -which, in turn, had resonances for them in Britain. Asian-language newspapers kept them in constant touch with events in the subcontinent, and the political refugees whom they housed and looked after not only involved them in their movements, but fired their own resistances. Reciprocally, their people back ’home’ were keened to the mounting racism in Britain.

*Such as the Naxalites, Adivasis, Dalit Panthers in India, and the Pakhtun, Sindhi and Baluchi oppressed people’s movements in Pakistan. In 1974 organisations of un- touchables in Britain came together at the (new) IRR to organise an International Conference on Untouchability (which for financial reasons never got off the ground).

On all these fronts, then, blacks by 1968 were beginning to fight as a class and as a people. Whatever the specifics of resistance in the respective communities and however different the strategies and lines of struggle, the experience of a common racism and a common fight against the state united them at the barricades. The mosaic of unities observed earlier resolved itself, before the onslaught of the state, into a black unity and a black struggle. It would recede again when the state strategically retreated into urban aid programmes and the creation of a class of black collaborators – only to be forged anew by another generation, British-born but not British.

In March 1968 the Labour government passed the ’Kenyan Asian Act’, this time barring free entry to Britain of its citizens in Kenya – because they were Asians. O.K. so they held British passports issued by or on behalf of the British government, but that did not make them British, did it? Now, if they had a parent or grandparent ’born, naturalised, or adopted in the UK’ – like those chaps in Australia, New Zealand and places – it would be a different matter. But of course the government would set aside a quota of entry vouchers especially for them – for the British Asians, that is. The reasons were not ’racial’, as Prime Minister Wilson pointed out to the Archbishop of Canterbury, but ’geographical’.

Between conception and passage the Act had taken but a week. The orchestration of public opinion that preceded it had gone on for about a year, but it had risen to a crescendo in the last six months. In October Enoch Powell, man of the people, had warned the nation that there were ’hundreds of thousands of people in Kenya’** who thought they belonged to Britain ’just like you and me’. In January the press came out with scare stories, as it had done before the Immigration Act of 1962, except that this time it was not smallpox but the clandestine arrival of hordes of Pakistanis . In February Powell returned to his theme – and other politicians joined in. Later in the month the Daily Mirror, the avowedly pro-Labour paper, warned of an ’uncontrolled flood of Asian immigrants from Kenya’. On 1 March the bill was passed.

*There were in fact about 66,000 at this time who were entitled to settle in Britain

Blacks were enraged. They had lobbied, petitioned, reasoned, demonstrated – even campaigned alongside whites in NCCI’s Equal Rights set-up – and had made no impact. But the momentum was not to be lost. Within weeks of the Act Jagmohan Joshi, Secretary of the IWA Birmingham, was urging black organisations to form a broad, united front. On 4 April Martin Luther King was murdered …’I have a dream …’ They slew the dreamer.

Some two weeks later Enoch Powell spoke of his and the nation’s nightmare: the blacks were swarming all over him, no, all over the country, ’whole areas and towns and parts of towns across England’ were covered with them, they pushed excreta through old ladies’ letter boxes; we must take ’action now’, stop the ’inflow’, promote the ‘outflow’, stop the fiances, stop the dependants, ’the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population’, the breeding ground. ’Numbers are of the essence.’

’What Powell says today, the Tories say tomorrow and Labour legislates on the day after.’ But, immediately, it was public opinion that was roused. The press picked up Powell’s themes and Powell. The unspeakable had been spoken, free speech set free, the whites liberated; Asians and West Indians were abused and attacked, their property damaged, their women and children terrorised. Police harassment increased, the fascists went on a rampage and Paki-bashing emerged as the national sport. A few trade unionists made feeble gestures of protest and earned the opprobrium of the rank and file. White workers all over the country downed tools and staged demonstrations on behalf of Powell. And on the day that even-handed Labour, having passed a genuinely racist Immigration Act, was debating a phoney anti-racist Race Relations Bill, London dockers struck work and marched on parliament to demand an end to immigration. Three days later they marched again, this time with the Smithfield meat-porters.

But the blacks were on the march too. On the same day as the dockers and porters marched, representatives from over fifty organisations (including the IWAs, WISC, NFPA, UCPA, RAAS, etc.) came together at Leamington Spa to form a national body, the Black People’s Alliance (BPA), ’a militant front for Black Consciousness and against racialism’. And in that, the BPA was uncompromising from the outset. It excluded from membership immigrant organisations that had compromised with government policy or fallen prey to government hand-outs (Labour’s Urban Aid programme was beginning to percolate through to the blacks) or looked to the Labour Party for redress. For, in respect of ’whipping up racial antagonisms and hatred to make political gains’, there was no difference between the parties or between them and Enoch Powell. He was ’just one step in a continuous campaign’ which had served to give ’the green light to the overtly fascist organisations … now very active in organising among the working class’. Member organisations would continue to maintain their independent existence and function at the local level, in terms of the particular communities and problems; the BPA would operate on the national level, coordinating the various fights against state racism. And, where necessary, it would take to the streets en masse – as it did in January 1969 (during the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference), when it led a march of over 7,000 people to Downing Street to demand the repeal of the Immigration Acts.

From Powell’s speech and BPA, but nurtured in the Black Power movement, sprang a host of militant black organisations all over the country, with their own newspapers and journals, taking up local, national and international issues. Some Jamaican organisations marched on their High Commission in London, protesting the banning of the works of Stokely and Malcolm X in Jamaica, while others, like WISC, RAAS and the Caribbean Artists’ movement, sent petitions. On the banning of Walter Rodney from returning to his bun post at the university, Jamaicans staged a sit-in at the High Commission. A ’Third World’ Benefit for three imprisoned playwrights – Wole Soyinka in Nigeria, LeRoi Jones in America and Obi Egbuna in Britain – was held at the Round House with Sammy Davis, Black Eagles and Michael X. But Egbuna’s imprisonment (with two other UCPA members), for uttering and writing threats to kill police, also stirred up black anger. ’Unless something is done to ensure the protection of our people’, wrote the Black Panther Movement in its circular of 3 October 1968 ‘ . . . we will have no alternative but to rise to their defence. And once we are driven to that position, redress will be too late, Detroit and Newark will inevitably become part of the British scene and the Thames foam with blood sooner than Enoch Powell envisaged.’*

*A reference to Powell’s Birmingham speech (April 1968) in which he said: ’As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman ,I see the River Tiber foaming with much blood’.

Less than six months after Powell’s speech, Heath, the Tory leader, having sacked Powell from the Shadow Cabinet, himself picked up Powell’s themes. Immigration, he said, whether of voucher-holders or dependants, should be ’severely curtailed’– and those who wished to return to their country of origin should ’receive assisted passage from public funds’. But Powell outbid him in a call for a ’Ministry of Repatriation’ and ’a programme of large-scale voluntary but financed and subsidised repatriation and re-emigration’. Two months later Heath upped the ante: the government should stop all immigration. Powell, who was on the same platform, applauded him. Callaghan, the Home Secretary, however, derided Heath’s speech as ’slick and shifty’. Three days later Callaghan debarred Commonwealth citizens from entering Britain to marry fiancés and settle here, ’unless there are compassionate circumstances’. And in May 1969, in an even more blatant piece of ‘even-handedness’, Callaghan sneaked into the ’liberal’ Immigration Appeals Bill* a clause which stipulated that dependants should henceforth have entry certificates before coming to Britain. And with that he set the seal on the prevarications, delays and humbug that British officials in the countries of emigration, mainly India and Pakistan now, subjected dependants to – till the young grew old in the waiting and old folk just gave up or died. It was a move in Powell’s direction, but he meanwhile had moved on to higher things, like calculating the cost of repatriation. Before Callaghan could move towards him again,Labour lost the election(1970).It was now left to a Tory government underHeathtoeffect Powellite policies (on behalf of Labour) in the Immigration Act of 1971.

The new Act stopped all primary (black) immigration dead. Only ‘patrials’ (Callaghan’s euphemism for white Commonwealth citizens, a concept propounded by the class of 1968) had right of abode now. Non-patrials could only come in on a permit to do a specific job in a specific place for a specific period. Their residence, deportation, repatriation and acquisition of citizenship were subject to Home Office discretion. But constables and immigration officers were empowered to arrest without warrant anyone who had entered or was suspected (’with reasonable cause’) to have entered the country illegally or overstayed his or her time or failed to observe the rules of the Act in any other particular. Since all blacks were, on the face of them, non- patrials, this meant that all blacks were illegal immigrants unless proved otherwise. And since, in this respect, the Act (when it came into force in January 1973) would be retrospective, illegal immigrants went back along way.

Entry of dependants of those already settled in Britain would continue to be made on the basis of entry certificates issued by the British authorities, at their discretion, in the country of emigration. Eligibility – as to age, dependancy, relationship to the relative in the UK, etc. – would have to be proved by the dependant. Children would have to be under 18 to be eligible at all and parents over 65. But ’entry clearances’ did not guarantee entry into Britain. It could still be refused at the port of entry by the immigration officer on the ground that’ false representations were employed or material facts were concealed, whether or not to the holder’s knowledge, for the purpose of obtaining clearance’ (emphasis added). * And as for those who wanted to be repatriated, every assistance would be afforded.

*When, in 1980, Filipino domestic workers who had entered legally were to ask to bring in their children, they would be deported – on the basis of this clause – for having withheld information (re children) which they were not asked for in the first place.

On the face of it, the Act appeared no more racist than its predecessors. Bans and entry certificates, stop and search arrests and ‘Sus’,** detentions and deportations were already everyday aspects of black life. Even the distinction that the Act made between the old settlers and the new migrants to make them all migrants again did not seem to matter much: they had never been anything but ’coloured immigrants’. But there was something else in the air. The ’philosophy’ had begun to change, the raison d’etre of racism.It was not that racism did not make for cheap labour any more, but that there was no need for capital to import it. Instead, thanks to advances in technology and changes in its own nature, capital could now move to labour,and did – the transnational corporations saw to that. The problem was to get rid of the labour, the black labour that was already here. And racism could help there – with laws and regulations that kept families apart, sanctioned police harassment, invited fascist violence and generally made life untenable for the black citizens of Britain. And if they wanted to return ’home’, assisted passages would speed their way.

**Under section 4 of the 1824 Vagrancy Act anyone could be arrested ’on suspicion’ of loitering with intent to commit an arrestable offence.

To get the full flavour of the Immigration Act of 1971, however, it must be seen in conjunction with the Industrial Relations Act of the same year. For if the Immigration Act affected the black peoples (in varying ways), the Industrial Relations Act, which put strictures on trade unions and subjected industrial disputes to the jurisdiction of a court, the National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC), affected the black working class specifically. As workers, they were subject to the Industrial Relations Act’s overall attack on the class (and later to the government’s three-day week). As blacks, they were subject to the Immigration Act’s threat of deportation – as illegal immigrants or for acting in ways not ’conducive to the public good’. As blacks and workers, they were subjected to the increasing racism of white workers and trade unions under siege – and more susceptible to being offered up to the NIRC for the adjudication of their disputes. Together, the Acts threatened to lock the black working class into the position of a permanent under-class. Hence, it is precisely in the area of black working- class struggles that the resistance of the early 1970s becomes significant.

But these were not struggles apart. They were, because they were black, tied up with other struggles in the community, which in turn was involved in the battles on the factory floor. The community struggles themselves had, as we have seen, become increasingly politicised in the Black Power movement and organised in black political groups. And they, after the failure of the white left to acknowledge the special problems of the black working class or the need for black self-help and organisation, began to address themselves to the problems of black workers – in the factories, in the schools, in their relationship with the police. Which in turn was to lead to more intense confrontation with, if not the state directly, the instruments of state oppression. But since these operated differentially in respect of the two main communities, except in the workplace, the resistance to them was conducted at different levels, in different venues, with (often) different priorities (again with the exception of the workplace).

The energies of the Asian community, for instance, were taken up with trying to get their families and dependants in – and once in, to keep them (and themselves) from being picked up as illegal im- migrants. Since these required a knowledge of the law and of officialdom, it was inevitable that their struggles in this respect would be channelled into legal battles – mainly through the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI)* with its expertise and commitment – and into petitioning and lobbying. This aspect was further reinforced by the issue of the ’shuttlecock Asians’, those British Asians in East Africa who (for one reason or another) were bandied about from country to country before eventually being imprisoned in Britain prior to admission.** From 1972 Asian leaders and organisations were also preoccupied with the resettlement of British Asian refugees from Amin’s Uganda.

*JCWI was set up in 1967 as a one-man welfare service for incoming dependants at Heathrow Airport, but later burgeoned into a case-work and campaigning organisation.

**According to a letter in the Guardian of 10 September 1981 from members of Jawaharlal Nehru University (Delhi), there are still ’20,000 people of Indian origin from East Africa … waiting in India for their entry vouchers to the UK’.

If the struggles to gain entry for their families and dependants drained the energies of the Asian community at one level, the abuse and the humiliation that those seeking entry were submitted to by immigration officials served to degrade and sometimes demoralise it. The instances are legion and have been documented elsewhere. But the most despicable of them all was the vaginal examination of women for virginity – in itself an appalling violation but, for women from a peasant culture, a violation beyond violence. Equally debilitating of the community was the police use of informers to apprehend suspected illegal immigrants individually and through ’fishing raids’, generating thereby suspicion and distrust among families. In turn, the battles against them channelled the community’s energies into getting the retrospective aspect of the Immigration Act regarding illegal immigrants repealed (and was finally ‘rewarded’ by the dubious amnesty of 1974 for all those who had entered illegally before 1973). But the police’s Illegal Immigration Intelligence Unit (IIIU) remained in force. The Afro-Caribbean community, for its part (and again excepting the workplace, which will be treated separately), was occupied with fighting the mis-education of its children and the harassment of the police. Both problems had existed before, but they had now gathered momentum. West Indian children were consistently and right through the schooling system treated as uneducable and as having ’unrealistic aspirations’ together with a low IQ. Consequently, they were ‘banded’ into classes for backward children or dumped in ESN (educationally subnormal) schools and forgotten. The fight against categorisation of their children as under-achieving, and therefore fit only to be an under- class, begun in Haringey (London) in the 1960s by West Indian parents, teachers and the North London West Indian Association (NLWIA) under JeffCrawford, now spread to otherareasandbecame incorporated in the programmes of black political organisations. An appeal to the Race Relations Board (1970) elicited the response that the placement of West Indian children in ESN schools was ’no unlawful act’. The Caribbean Education Association then held a conference on the subject and in the following year Bernard Coard (now Deputy Prime Minister of Grenada) wrote his influential work, How the West Indian child is made educationally subnormal … Black militants and organisations, meanwhile, had begun to set up supplementary schools in the larger conurbations. In London alone there was the Kwame Nkrumah school (Hackney black teachers), the Malcolm X Montessori Programme (Ajoy Ghose), the George Padmore school (John La Rose* and the Black Parents’ Movement), the South-east London Summer School (BUFP: Black Unity and Freedom Party), Headstart (BLF: Black Liberation Front) and the Marcus Garvey school (BLF and others).**

*John La Rose had been Executive of the Federated Workers’ Trade Union in Trinidad and Tobago.

**It was one of the founders of this school, Tony Munro, who was later to be involved in the Knightsbridge Spaghetti House siege.

Projects were also set up to teach skills to youth. The Mkutano Project, for instance, started by the BUFP (in 1972), taught typing, photography, Swahili; the Melting Pot, begun about the same time by Ashton Gibson (once of RAAS), had a workshop for making clothes; and Keskidee, set up by an ex-CARD official, Oscar Abrams, taught and sculpture and encouraged black poets and playwrights. For older students, Roy Sawh ran the Free University for Black Studies. And then there were hostels for unemployed and homeless black youth – such as Brother Herman’s Harambee and Vince Hines’ Dashiki (both of whom had been active in RAAS) – and clubs and youth centres. Finally, there were the bookshop cum advice centres,such as the Black People’s Information Centre, BLF’s Grassroots Storefront and BWM’s Unity Bookshop,* and the weekly or monthly newspapers: Black Voice (BUFP), Grassroots (BLF), Freedom News (BP: Black Panthers), Frontline (BCC: Brixton and Croydon Collective), Uhuru (BPFM: Black People’s Freedom Movement), BPFM Weekly, the BWAC Weekly (Black Workers’ Action Committee) and the less frequent but more theoretical journal Black Liberator – and a host of others that were more ephemeral. Some of these papers took up the question of black women, and the BUFP, following on the UCPA’s Black Women’s Liberation Movement, had a black women’s action committee

*The BWM (Black Workers’ Movement) was the new name the Black Panthers took in the early 1970s.

RAAS’s Black House was going to be a huge complex, encompassing several of these activities. But hardly had it got off the ground in February 1970 than it was raided by the police and closed down. And RAAS itself began to breakup. Members of RAAS,however,went on to set up various self-help projects – as indicated above.

By 1971 the UCPA was also breaking up into its component groups, with the hard core of them going to form the BUFP. (National bodies were by now not as relevant to the day-to-day struggles as local ones and the former’s unifying role could equally be fulfilled by ad hoc alliances.) The UCPA, RAAS, the Black Panthers and other black organisations had in the previous two years been increasingly occupied with the problem of police brutality and fascist violence.The success of Black Power had brought down on its head the wrath of the system.Its leaders were persecuted, its meetings disrupted, its places of work destroyed. But it had gone on gaining momentum and strength: it was not a party, but a movement, gathering to its concerns all the strands of capitalist oppression, gathering to its programme all the problems of oppressed peoples. There was hardly a black in the country that did not identify with it and, through it, to all the non-whites of the world, in one way or another. And as for the British-born youth, who had been schooled in white racism, the movement was the cradle of their consciousness. Vietnam, Guinea-Bissau, Zimbabwe, Azania were all their battle-lines, China and Cuba their exemplars. The establishment was scared. The media voiced its fears. There were rumours that Black Power was about to take over Manchester City Council.

In the summer of 1969 the UCPA and the Caribbean Workers’ Movement were documenting and fighting the cases of people beaten up and framed by the police – in Manchester and London. In August the UCPA held a Black Power rally against ‘organised police brutality’ on the streets of Brixton. In April 1970 the UCPA and the Pakistani Progressive Party staged a protest outside the House of Commons over ’Paki-bashing’ in the East End of London. And the Pakistani Workers’ Union called for citizens’ defence patrols: a number of Asians had been murdered in 1969 and 1970. A month later over 2,000 Pakistanis, Indians and West Indians marched from Hyde Park to Downing Street demanding police protection from skinhead attacks. In the summer of 1970 police attacks on blacks – abuse, harassment, assaults, raids, arrests on ’Sus’, etc., in London, Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham, Leeds, Liverpool, etc., put whole black communities under siege. In July and August there were a series of clashes between black youth and the police in London and on one occasion over a hundred youth surrounded the Caledonian Road police station demanding the release of four blacks who had been wrongfully arrested. Things finally came to a head in Notting Hill on 9 August, when police broke up a demonstration against the proposed closure of the Mangrove restaurant with, even for them, unprecedented violence. The blacks fought back, a number of them were arrested and nine of the ’ring- leaders’ subsequently charged with riot, affray and assault.

The Mangrove was a meeting place and an eating place,a social and welfare club, an advice and resource centre, a black house for black people, a resting place in Babylon. And if only for this reason, the police could not leave it alone. They raided it and raided it, harassed its customers and relentlessly persecuted its owner, Frank Critchlow. They made it the test of police power; the blacks made it a symbol of resistance. The battle of the blacks and the police would be fought over the Mangrove.

The trial of the Mangrove 9 (October-December 1971) is too well documented to be recounted here, but, briefly, they won. They did more: they took on what the defence counsel called ’naked judicial tyranny’ -some by conducting their own defence -and won. Above all, they unfolded before the nation the corruption of the police force, the bias of the judicial system, the racism of the media – and the refusal of black people to submit themselves to the tyrannies of the state. Other trials would follow and even more bizarre prosecutions be brought, as when the alleged editor of Grassroots was charged with ’encouraging the murder of persons unknown’ by reprinting an article from the freely available American Black Panther paper on how to make Molotov cocktails. But they would all be defended – by the whole community – and become another school of political education. *

The Mangrove marked the high water-mark of Black Power and lowered the threshold of what black people would take, it also marked the beginnings of another resistance: of black youth condemned by racism to the margins of existence and then put upon by the police. ’Sus’ had always laid them open to police harassment, but the government’s White Paper on Police-Immigrant Relations in 1973, which warned of ’a small minority of young coloured people … anxious to imitate behaviour amongst the black community in the United States’, put the government’s imprimatur on police behaviour. The previous year the press and the police had discovered a ’frightening new strain of crime’ and ’mugging’ was added to ’Sus’ as an offence on which the police could go on the offensive against West Indian youth. The courts had already nodded their approval – by way of an exemplary twenty-year sentence passed on a 16-year-old ’mugger’. From then on, the lives of black youths in the cities of Britain were subject to increased police pressure. Their clubs were attacked on one pretext or another, their meeting places raided and their events – carnivals, bon- fires, parties – blanketed by police presence. Black youths could not walk the streets outside the ghetto or hang around streets within it without courting arrest. And apart from individual arrests, whole communities were subjected to road blocks, stop and search and mass arrests. In Brixton in 1975 the paramilitary Special Patrol Group (SPG) cruised the streets in force, made arbitrary arrests and generally terrorised the community. In Lewisham the same year the SPG stopped 14,000 people on the streets and made 400 arrests. The pattern was repeated by similar police units in other parts of the country.

The youth struck back and the community closed behind them at Brockwell Park fair in 1973, for instance, and at the Carib Club (1974) and in Chapeltown, Leeds,on bonfire night (1975),and finally exploded into direct confrontation, with bricks and bottles and burning of police cars, at the Notting Hill Carnival of 1976 – when 1,600 policemen took it on themselves to kill joy on the streets.

Clearly the politics of the stick had not paid off – or perhaps it needed to be stepped up to be really effective. But by n o w a Labour government was in power and the emphasis shifted to social control.

Meanwhile, the struggles in the workplace were throwing up another community, a community of black class interests – linking the shop- floor battles of Pakistanis, Indians and West Indians, sometimes directly through roving strike committees, sometimes through black political organisations, while combating at the same time the racism of the trade unions, from within their ranks. Where they were not unionised, blackworkers first used the unions,who were rarely loth to

increase their numbers, however black, to fight management for unionisation – and then took on the racism of the unions themselves. Unions, after all, were the organisations of their class and, however vital their struggles as blacks, to remain a people apart would be to set back the class struggle itself. They had to fight simultaneously as a people and as a class – as blacks and as workers – not by subsuming the race struggle to the class struggle but by deepening and broadening class struggle through its black and anti-colonial, anti-imperialist dimension. The struggle against racism was a struggle for the class.

A series of strikes in the early 1970s in the textile and allied industries in the East Midlands and in various factories in London illustrate these developments. In May 1972 Pakistani workers in Crepe Sizes in Nottingham went on strike over working conditions, redundancies and pay. They composed the lowliest two-thirds of the workforce, were subjected to constant racial abuse by the white foreman and worked, without adequate safety precautions and toilet and canteen facilities, an eighty-four-hour week for £40.08. And yet five of their number had been made redundant – not fortuitously, after the workers had joined the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU). There was no official support from the union, however, till a Solidarity Committee composed of the wives and families of the strikers and of other Asian workers, community organisations and the Nottingham-based BPFM forced the TGWU to act. In June the management capitulated, agree- ing to union recognition and the re-instatement of the workers who had been made redundant.

The strike of Indian workers at Mansfield Hosiery Mills in Loughborough in October 1972 was for higher wages and against the denial of promotion to jobs reserved for whites. The white workers went along with the wages claim but not promotion, and the union, the National Union of Hosiery and Knitwear Workers, first prevaricated and then decided (after the strikers had occupied the union offices) to make the strike official, but not to call out the white workers. Once again, community associations, Asian workers at another company factory and political organisations like the BPFM and the BWM provided, in the Mansfield Hosiery Strike Committee, the basis for struggle.