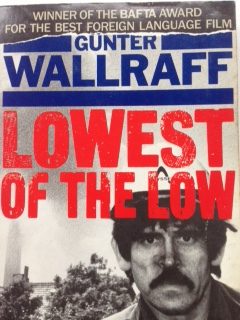

An Introduction to Lowest of the Low by Gunter Wallraff (Methuen 1988)

There is a massive sea-change going on within society as it moves from an industrial to a technological epoch. The immensity of that transition and its implications are still to be understood, by socialism in particular, but its immediate impact has been to render the working class fragmented, divided and weak, while cohering capital for another lease of life.

It is as though we have been set back in a time warp to the beginning of the industrial revolution, when the lives of working people were so degraded and desperate that they had to fight their way up through hard, long, concerted effort and union organisation to gain even a modicum of return for their labours and some little human dignity for their selves. Now they have it all to do again, but on a different basis and through different modes of organisation. What these are becomes clearer as capitalism’s new social project becomes unveiled. But the technology that allows of such a project is also the technology that allows capital to be informed without informing, survey without being surveyed and keep its machinations secret – not least through a media that propagates a culture of indifference and promotes a politics of disinformation.

The Fourth Estate no longer even pretends to reveal the deceits of power or investigate the predicament of the powerless, nor journalists try to take us to the heart of a matter. Wallraff, in terms of tradition, may well be the last of a line, but in the way he immerses himself in his subject while standing outside it – in his own skin – looking at the system that makes such subjects possible, he is the progenitor of a new. For it is only such a mix of drama and documentary, of investigative and campaigning journalism, of turning cases into issues, that can now break through the cordon sanitaire of the mass media and speak directly to the public about the matters that concern them (if only they knew). And when those he has exposed take up arms against him and use the whole panoply of power – from threats to his person and law suits, to media and state reprisal — to discredit him or vilify him or in some way still his voice, he gathers to himself a public that now calls into question the institutions of society and the apparatuses of the state. And the crusade is no longer that of one man, but of a nation.

In his previous avatars, Wallraff has variously hired himself as a labourer to a landed aristocrat to expose feudal work relations, in filtrated factory management in the guise of a ministry official to show how industry is developing its own armed units to defend itself against worker militancy; passed himself off as an extreme-right German financier, with arms and aid at his disposal, to uncover Spinola’s planned coup to re-establish fascism in Portugal; and re-entered into himself as a journalist to investigate the yellow journalism of Bild-Zeitung (and its ilk) and show how it manipulates news in order to keep its readership in a state of ignorance and so make them a party to their own defeat. ‘It cons its readers so well”, says Wallraff, ‘that they take pleasure in being kept down.’ And in the course of these journeys into truth, Wallraff uncovers too the complicity of the church and of the state in keeping the powerless powerless.

Here, in his latest journey, his most recent incarnation, Wallraff is Ali, an immigrant Turkish worker, the lowest of the low, the under-class, the lump. And like any Turkish worker (legal or otherwise), he is hired and fired, sat upon and spat upon, used and abused, vilified, reified and thrown on a heap (in Turkey preferably) when he is done with. And like all foreign workers the jobs he gets to do are, by and large, dirty, dangerous, temporary, exhausting, ill-paid and, often, illicit. The least of these is in the sundry jobs he carries out for small private employers or even for McDonalds where he turns over endless hamburgers on a red-hot grill in spitting fat, for a pittance. But it is when, like most foreign workers, he ends up on building sites and factories that he finally understands that he is no more than a unit of labour in the keeping of a subcontractor, who hires him out at will to a contractor who has contracted to do the shit work for reputable firms who want to remain reputable. He unblocks lavatories on work sites ankle-deep in piss and covered in racist graffiti; removes ‘half-frozen mounds of sludge from giant pipes high up on buildings (without protective helmet or clothing) in 17 degrees of frost: shovels (and inhales) coke dust hour after hour below ground level; is sent into areas filled with noxious gases (the supervisor asserting that the test machines registering dangerous levels can’t be right’); is made to crawl into a pig-iron ferry to clear a blockage with pneumatic tools and no mask. And when one gruelling shift is over, he is forced into another with no time for rest or for sleep.

Ali/ Wallraff has a choice, though; his fellows have none. They are permanently foreign, even if, like Yüksel, they have lived in Germany for twenty years, or they are permanently illegal because the only jobs they can get are illicit jobs and the only way they can remain in work is to remain illicit. All of which delivers them into the hands of the labour contractors who, in employing them illegally, without registration or insurance, are able also to filch their wages, of which, when every employer and subemployer and sub-subemployer has his cut, there is hardly anything left. There is only work-hard, endless, back-breaking, soul-searing work – that clogs up the lungs with dust and suffuses the system with heavy metal poisoning and, if you are lucky to find a comparatively light job like cleaning out a nuclear power station, leaves you with a lingering cancer that might only be discovered long after you have returned ‘home’. Or you might hire your body out to the pharmaceutical industry to be experimented on with risky combinations of drugs that would not necessarily advance the cause of science but would certainly provide new and expanded markets for old products under new names.

The unacceptable face of the Turk hides also the unacceptable face of capitalism. The racism that defines him as inferior, fit only for dirty jobs and disposable, and locks him permanently into an under-class, is also that which hides from the public gaze the murkier doings of industry. And contracting out the shit work allows management itself to avert its face from its own seamy activities. That also saves it from the legal consequences of employing unregistered, uninsured workers and/or transgressing safety regulations — for these are the responsibility of the firm that hires out the labour. But since that labour is alien, foreign, and therefore rightless, the law does not want to know. Nor does the government, which wants the work – cheap, unorganised, in visible – but not the workers. And all the complicated legislation and regulations regarding foreign workers, since the Gastarbeiter system broke down in the early 1970s,’ have pointed to a policy which builds repatriation into every aspect of the ‘immigrant’s’ life from schooling to work and even perhaps to death and burial.

A whole system of exploitation is thus erected on the back of the foreign worker, but racism keeps it from the light of day. It is that same racism, popular and institutional, that keeps the unions too from taking up the cause of foreign workers – and the contribution of the media and of politicians in making it popular keeps them forever foreign.

And the Church yields no succour. It is indifferent to the problems of the most needy in modern society. Ali cannot even be baptised into Catholicism because that would make him less foreign, more legal. If only he were less foreign and more legal in the first place … Besides, what binds the Church, like the unions, is structure, ritual, protocol. It could not just pick up any old cause from off the street. Where would it be if it took up Ali’s cry, I say Christ for the persecuted.’ Or, as Wallraff bitterly comments, ‘It’s enough having to put up with them in our schools, suburbs and railway stations. Our churches, however empty they are, must remain free of Turks, and clean.’

Nor does the constantly changing, ad hoc nature of their work permit them to organise on their own behalf. Seldom are the same workers allowed to do the same job or work in the same place for too long, and, even when they do, they are required to speak to each other only in Geman so that the ‘sheriff’ knows what they are up to. Some of them besides are illegals or asylum-seekers and are fearful of being sent back to a fascist dictatorship with which the German state has a special relationship.

Wallraff, in unravelling one thread, unravels the whole fabric of Ger man society; in using deception to uncover deception, makes a case for open government; and in revealing the condition of the meanest worker, reveals the state of the nation.

He does more. He casts light on how the technological revolution has enabled advanced industrial countries like Germany to export less profitable industries to the cheap labour pools of the Third World, whilst importing what Wallraff himself calls a ‘disposable, interchangeable’ workforce to clean up the excrement of silicon-age capitalism. And that workforce increasingly comes, not from the classic reserve armies of labour once thrown up by colonialism and uneven development, but from the flotsam and jetsam of political refugees thrown up by rampant imperialism. The fascist dictatorships that western powers set up and maintain in Third World countries in their own cold-war interests are also those that provide the West with the rightless, homeless, peripatetic labour it needs. Turkey is a case in point.

Wallraff himself denies that he has a political axe to grind. He is not a marxist and he is ‘hostile to theory and against ideology’. He is motivated instead by ordinary Christian principles. But there is a politics in stories truthfully told. And the truth in Wallraff’s story comes from his wholesale immersion in his character. There is not two of him except in the laying of the words on the page, Ali and Wallraff, only Ali-Wallraff. The humiliation he suffers as Ali – ‘Stop animal experiments, use Turks”, reads a slogan – is the shame he suffers as Wallraff. The hate directed at Ali by his German fellows – ‘an SS-pig is better than a Turkish bastard’ – is the pain Wallraff endures as a fellow German. The hostility visited on Ali as a foreigner is the horror that Wallraff feels for an unrepentant Germany: ‘There never was a better German than Adolf Hitler.’

Wallraff, like Benjamin’s storyteller, ‘is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself”.