The Colour Line is the Poverty Line

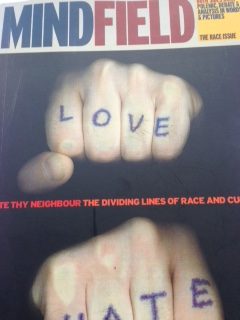

Based on an Interview for ‘Hate thy neighbour: the dividing lines of race and culture‘ in the Mindfield Series edited by Susan Greenberg (Camden Press 1998).

In the 1970s, A. Sivanandan battled to change the Institute of Race Relations from what he considered to be an arid, academic pro-government body into a committed anti-racist think-tank. For over 30 years he has campaigned against racism in the criminal justice and educational systems, fought aganist fascist groups and contributed to many community campaigns. When the wave of radical activism receded in the 1980s, Sivanandan was one of the few to remain on the campaigning trail. Like many others, MindField came to him with the idea of including a class-based approach to the issue, but Sivanandan does not like to be boxed into categories:

”I am essentially a pamphleteer, writing for the occasion and interested in how to change things. I am not a theorist per se, although theory does come out of practice. So it is very difficult to locate me, although I remain true to certain basic principles.”

Can racism be explained as a rational way of pursuing self-interest? Is that the same as economic self-interest?

The question itself may be wrong. The racism I am concerned with is racial injustice which is institutionalised and structured, in legislation, the judicial system, schools, the way we police people…It is racial injustice that I want to combat, not personal prejudice, which I describe as racialism.Prejudice alone is an individual matter: it is the acting out of prejudice in a social context which constitutes discrimination. When discrimination is institutionalised, for example through a bad law against asylum seekers, that becomes racism and begins to reproduce itself in popular culture. I am not interested in the hatreds and prejudices of individuals. I don’t care whether white people love me or not, as long as I can send my child to their schools, walk the streets, buy a house if I can afford it.I want the same civil rights, the same justice, that white people get.I don’t ask for more. Racism is about power-institutional power, not personal power-and in that context the term “self-interest” becomes a misnomer. We are talking about how racial injustice becomes structured into society. In our time, all such inequalities are tied up with a system of economic exploitation called capitalism, so my fight is also against the capitalist system. If I was living under another system which had institutionalised racism, I would fight that too. The fight against racism has also to be a fight against poverty and class injustice, for a better society. It is a great egalitarian project. It has nothing to do with personal hatreds.

Racism, besides, is always in flux. It takes different forms in different times, from economic boom to depression, in different areas from the inner city, to the suburbs or rural areas, in different sectors from housing to employment and schooling. Then there is the racism visited on third world peoples and tied up with colonialism, there is post-independence communalism and ethnic cleansing, and there is current day globalisation which increasingly ties up racism with poverty.We cannot generalise about racism across the board, and across time. That would be ahistorical.

In recent writings, you have talked about being in a post-industrial era. What does that mean? Is racism “better”or “worse” in such an era?

I am not happy with the term post industrial. What I mean by it is that we

have moved from a society where labour was crucial to industrial production to one

in which labour is increasingly displaced by technology, disaggregated in its workplace

and disseminated all over the globe. Factories are no longer fixed in place and

time. They are also spread all over the globe, and capital can take up its plant and

walk to any part of the world where labour is cheap and captive and plentiful

Such transnational corporate capital, unlike colonial capital, is not interested in

the people it exploits. All it is interested in is profit. Hence the discrimination visited

on third world people is that much more absolute and violent. It is a racism tied up

with poverty and powerlessness. That is the fundamental difference between the racism

of industrial society and post-industrial society,the globalisation of racism.

And that is the same racism that is reproduced in Britain and within Europe,

because the process through which transnational corporations are able to

make profit in third world countries is also the process that throws up political

refugees and asylum-seekers on the shores of Europe. In other words, if multinationals

are to have a captive labour force, they must also have a captive regime, set up

and/or sustained by western powers.Consequently, the fight against these

regimes on the ground has become more difficult. In Nigeria, for example, the

opposition has been imprisoned or killed and its leader Ken Saro-Wiwa, who fought

the environmental ravages of the Shell oil company, was hanged. Without Shell, General

Abacha would be nothing.Without Abacha, Shell would not be in Nigeria. And that is

why I say: “It is your economics that makes our politics that makes us refugees in your

economies.” There is no such thing as illegal immigrants, only illegal governments.

But for migrants nowadays the conditions are very different from those

of the postwar era, when labour was needed, the working class had clout and

black people in Britain had citizenship and attendant rights. The refugees and

asylum-seekers of today are not even on the margins of society: they are outside

society. They have no citizenship rights no welfare rights, no legal rights, no rights

at all. They can only survive through illegal activities in the underground economy

where they are subjected to exploitation by employers and persecution by racists.

The EU, in denying access to welfare and rights, is effectively encouraging the

growth of a black economy with 19th-century working conditions. It is there

that exploitation is at its worst and racism at its most virulent.And yet, it is a racism

that goes unnoticed because it is an underground racism, invisible like the out-of

sight racism visited on workers in the third world.

At the same time, the struggle against racism in post-industrial society

has moved from the economic to the cultural sphere. The fight against racism has

been replaced by a fight for culture. The fight for economic and racial justice has

ceded to the post-modernist craze for a place in the cultural sun.

There has been a development in your thinking: before you simply criticised the post-modernists, now you seem to accept them as inevitable.

Yes, these are the times we are in — at least until we change them. Post-modernism is there, we have to deal with it.And it is there firstly because the technological revolution has made the cultural factor more dominant than the economic.

Secondly, we live in an information society, both in terms of information fed to machines which helps the process of production, and information fed to us through the media, which persuades us into accepting the status quo. And in such a society it is the cultural workers knowledge workers, systems analysts-the intelligentsia-who are in the engine room of power. The shift in emphasis from the economic to the cultural reflects the shift from the industrial to the information society. That is why Rupert Murdoch, not Britannia, rules the waves. That is why the whole question of racism has been taken away from the economic realm and vested in the cultural. And it is in that context that we have got to investigate theories like post-modernism.

For the post-modernists, the issue of race has become an abstraction. They are

not interested in, or even believe in, struggle and transformation. There is a

rejection of terms like black or racism which were honed in struggle, and a

preoccupation with the language surrounding “the racialisation process”.I am

not dismissing what these people are saying n terms of describing society, but they

don’t have a prescription for what ails society. This is another disease of post

modernism: there is no cause and effect I want a diagnosis out of which a prognosis

can be made, out of which I can find a prescription to change society. Post modernists don’t change the world, they change the interpretation. Racism, for them, is not linked to something like class or capitalism. It is not about injustice. It is simply about difference and accepting difference. Racism has been severed from its concrete forms of discrimination, brutality, media misrepresentation.

Racism is no longer what is done to people. Racism is being redefined as discourse.

Hence they applaud the cultural fusion, the “rich mix” which they see taking place

in Britain today,the cultural “negotiation” between mainstream society and ethnic

minorities that allows the latter to be themselves but also British. But they are

completely oblivious to the fact that there are whole sections of ethnic minorities

mired in poverty and racism.

Today we have two racisms: the kind that discriminates and the kind that kills.

Because of past struggles we have the tools to fight the first. It is the second

kind I am worried about, that which affects refugees and the never-employed youth of

our inner cities. The black writer WEB. Du Bois once said that the most important

thing about the 20th century was the colour line. Today, the colour line is the

power line is the poverty line. It is in the inner cities, where people are competing

for a handful of houses and jobs and the BNP feeds off such disaffection, where

black kids like Stephen Lawrence, Rohit Duggal and Manish Patel are being killed

that racism is at its most intractable. But no one addresses that kind of racism any

more, except a few local groups which are trying to create communities of resistance

that cut across ethnic and religious divides.

Why is no one dealing with it? Why the fragmentation?

In the 1960s and ’70s, we found common denominators through our common colonial experience and working class jobs, and black became a political colour. People found their identity through socialisation at work, through struggles in the workplace-against

racial discrimination, for better working conditions, for a higher standard of living

and so on. That began to break down when the fight against racism became the fight

for culture or ethnicity and, from there,a fight for identity.At a time of unemploy-

ment, identity is formed not at work but in the cultural arena. So the birth of identity

politics is not an accident.It is tied up with the move from the economic to the cultural.

On the larger canvas, the contradiction of our time is that while capital is looking

to globalise, people are looking to localise. Hence the breaking down of national barriers on the one hand, and, on the other, the breaking up of nation states into their

ethnic or national components, as in Rwanda, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, the

Soviet Union, even the United Kingdom.In such a situation we look for something to

hold on to, and cultural ties such as religion become important. Here in Britain, we are going through a period when we are retreating into ourselves. We don’t fight racism, we fight for individual rights of expression.”The personal is political” is taken to extremes:

people think that, if I am gay and fight for gay rights, I am taking on the system; if I

am a Muslim and stop my factory work to pray at various times of the day, that is

taking on the system. But that does not affect the system at all. Britain is an old

democracy, a blotting paper society which absorbs and negates such protests. It is no

problem if you want to wear dreadlocks you might even get a grant!

Cultural politics alter things on the surface, but do not alter unemployment,

housing shortages and so on. These are things that need to be changed at the

poverty level of society. That is where communities of resistance are forming.Right

now it is a handful of people, but new formations are taking place, for example around

the environment, welfare cuts and so on. But we have to find the common denominators that opens us to each other’s struggles. It is a long process, but it will come.

Even if you find another common denominator, there are real differences felt by different communities. For example, Asian intellectuals are questioning what they consider to be a “black” anti-racism model.

Intellectuals always come when the battle is over on the ground; then they tidy up and

make theories over the dead bodies of their subjects. After the inner city riots of 1981

and the Scarman report, money was made available for the “racially disadvantaged”.

In practice this came to be defined in ethnic terms and a battle ensued between

African, Asian and Afro-Caribbean groups as to who was more eligible for funding.

The intellectuals then came along and mounted the rationale for ethnic

pragmatism in theories of difference. Now, black groups think they have nothing

in common with Asians, and Asians are saying there is no such thing as black.

Of course there are real differences felt by different communities-there

always have been-and these can be divided and sub-divided to the last entity. The

question, however, is whether you want to improve your lot within society or change

society to improve everyone’s lot. The post-modern intellectuals, ethnic or otherwise,

stand against any such universalising principle. They have found a philosophical justi-

fication for rejecting the politics of blackness and, in the process, have found

a justification for not being engaged in political struggle at all. The term black

itself emerged as a political metaphor and I still use it in that sense. Those Asians who

object to being called black are objecting not so much to a racial categorisation as

to the radicalism of the politics associated with the term.

As for a “black”anti-racism model, there is no such thing as anti-racism, no

ideology, no dogma and no model — only a thousand ways of fighting racism. Models

don’t interest me.Ideologies don’t interest me. Theories don’t interest me. I am interested in the fact that there is racism which we can fight on a common basis of fighting injustice, whoever we are, because we want a better society. How you do it is up to you. The subjective situation tells me how I fight. The objective situation tells me what I fight.I don’t care who or what people are as long as they are fighting the same thing as me.

What is your response to the argument that “PC” attitudes have made it hard for white youths to develop a positive identity around their own culture: that you cannot love others unless you love yourself?

The argument is that white youths such as those in Greenwich, where Stephen

Lawrence was killed, have no sense of identity. But they do, it is a racist one: they

are proud of it. Love yourself, yes, but for the right reasons. This argument is giving

an alibi to racism, making it respectable through the back door. The answer is not

to deracialise policy. The answer is to fight the trend towards ethnicism, culturalism,

religious fundamentalism. We must go on arguing that the more hybrid things are,

the more alive they are, that there is no such thing as a “pure” culture. The mistake of the black movement was to let anti-racism turn into multiculturalism. By exalting everything ethnic, they denigrated everything white: every white person became racist until proved innocent. It is multiculturalism, not anti-racism, which denies white youths a habitation and a name. The fight against racism, I repeat, is not a fight for cultural enclaves but a fight against racial injustice, against inequality, against freedom for some and unfreedom for others.

There was a mood of hopefulness around the Labour victory of 1997. Is anything good likely to come from that?

There is hope because people got rid of a government representing the principle

of selfishness that dominated a whole generation. But the politics of selfishness

has been replaced by the politics of consensus, and that stops hope from

becoming effective, as much as the politics of selfishness kills hope altogether.

Put it another way. There is hope because officially, individualism has died

But the market has not died. Labour says it will control the market, but there are

contradictions in that position.And it is our business to exploit those contradic-

tions. If you offer to speak for the poor and socially excluded and still maintain the

dictatorship of the market, you soon get to the sticking point of raised expectations

and no delivery,and people get impatient restive.And there is hope in that.

I do not think it is human nature to despair… There’s no such thing as pessimism of the intellect, as Gramsci is always quoted as saying. If you are alive you have no business not to hope. That is the burden of being human. Otherwise you are an animal.We hope, we love, we imagine, we grow, we are gods, we are poets. We all are. To the extent that the system stops us from achieving our possibilities, I fight the system.