On 13 January 1970, three black prisoners in Soledad Prison, California, were shot dead by a white guard. Three days later, 45 minutes after these killings were declared to be justifiable homicide, another guard was found dead. Three prisoners, George Jackson, John Clutchette and Fleeta Drumgo – now known as the Soledad Brothers – were charged with murder.

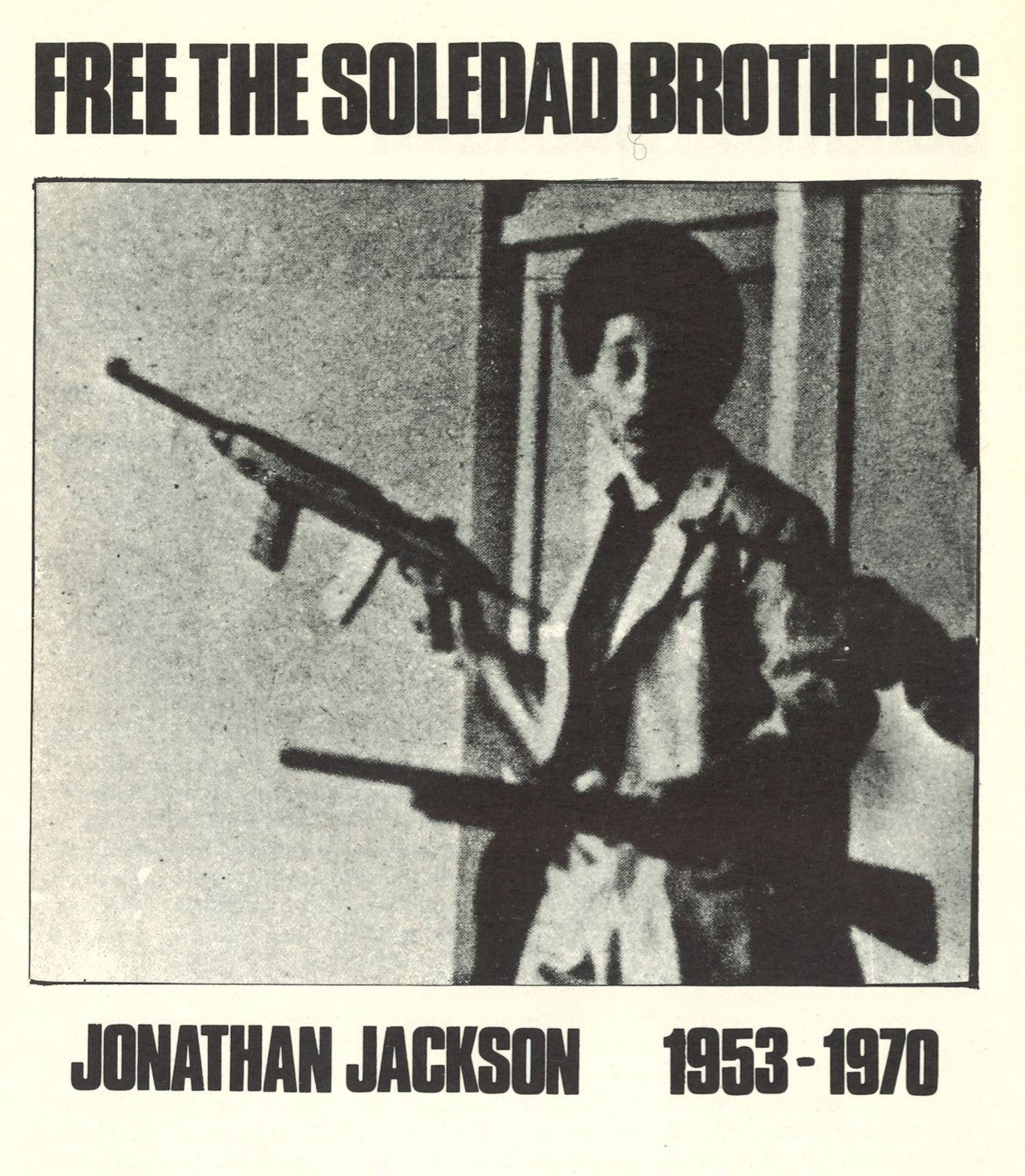

On 7 August 1970, Jonathan Jackson, George’s younger brother, in an attempt to force the authorities to free the Soledad Brothers, held up the Marin County Court in San Rafael, California, where James McClain, a San Quentin prisoner was on trial: he handed guns to McClain and the two witnesses, William Christmas and Ruchell Magee – also prisoners – and took two jurors and the judge as hostages. As they were about to drive away, the police opened fire, killing Jonathan, William, James and the judge.

He was seven when they took his brother from him – his big brother – and put him in jail because, or so they said, he had stolen $70 from a petrol station. The boy did not believe it: they themselves would soon realise their mistake and send his brother back home to him.

But the years went by and George did not return. They kept him in prison on one pretext or another. Jonathan, now going on fourteen, became fearful for his brother. At the Catholic primary school to which his parents had sent him, hoping in their love to spare him the burden of his blackness, he had been a promising pupil and a popular one. At Pasadena High, Jonathan had fought his first battle: a boy had made foul remarks about black people. By the time he was transferred to Blair, the world had begun to close in on him: the grief of the ghetto had crept into his heart, his brother’s predicament possessed his mind. He saw that his parents and his sisters could not help: they were defeated at every turn, beaten back by the system, fobbed off by their congressmen. He looked for understanding to his teachers at Blair. They did not care. No one cared – and those who cared were powerless to do anything. Even Fay Stender, George’s devoted lawyer, what could she do in the end? George was headed for the gas chamber.

In despair, Jonathan walked the courts of Los Angeles looking for a modicum of justice to assuage his disbelief. But he came back hurt, disillusioned, more wounded than before. “That judge sits there, Momma, and says no to everything. He doesn’t even stop to think before he says no.” And if there was no justice in the courts, where could a man turn to? George, Jonathan knew with a blinding certainty, was going to be killed: if the prisons did not get him, the courts would.

It all devolved on him now. He had to take up the burdens of justice and love and liberation – for himself, for George, for his people, for oppressed people everywhere. And so he stood there, that morning of August 7th 1970 – a boy barely turned seventeen – in the Marin County Courthouse, gun in hand, a judge as hostage (for how else could he set justice free?), demanding that the Soledad Brothers be freed by 12.30. Minutes later Jonathan was dead. But even as he died a moment of justice flickered like a miracle through America – and “the moment of a miracle is unending lightning.”